Dripping 2025 reconfigured my festival calculus

Discomfort, acceptance, surprise, and exaltation in the woods of New Jersey.

There was a spider in the tent, or so Nicole said. I couldn’t see it. It was dark, it was raining, and I felt like an old dishrag that had been soaked and wrung out to dry about six or seven times in a row—which was approximately the number of water bottles I had sweated through in process of burning up a six-month cache of serotonin on the dancefloor that night.

I’m not afraid of spiders, but I was getting worked up. I was—if you’ll forgive me—bugging out. It’s going to crawl all over me, I thought, and I would prefer it not to. (I’m not exactly a professional camper, as you may intuit.) Eventually I acquiesced, because what else was I going to do? I was still vibrating, but I had to try and sleep.

By the time I awoke the next morning, the rain had abated, I felt surprisingly decent, and I was totally unbothered by the eight-legged lil guy, whether he had ever actually been there or not. Something had shifted. I was ready for whatever would come next. I had locked in, as they say in the parlance.

Discomfort; acceptance; surprise; exaltation—that sums up my time at Dripping, a multivalent music and performing arts camping festival in the woods of New Jersey, now in its third year. It was neither an easy nor inexpensive experience, but it was a singular musical and artistic encounter that has me rethinking what I want from music festivals going forward.

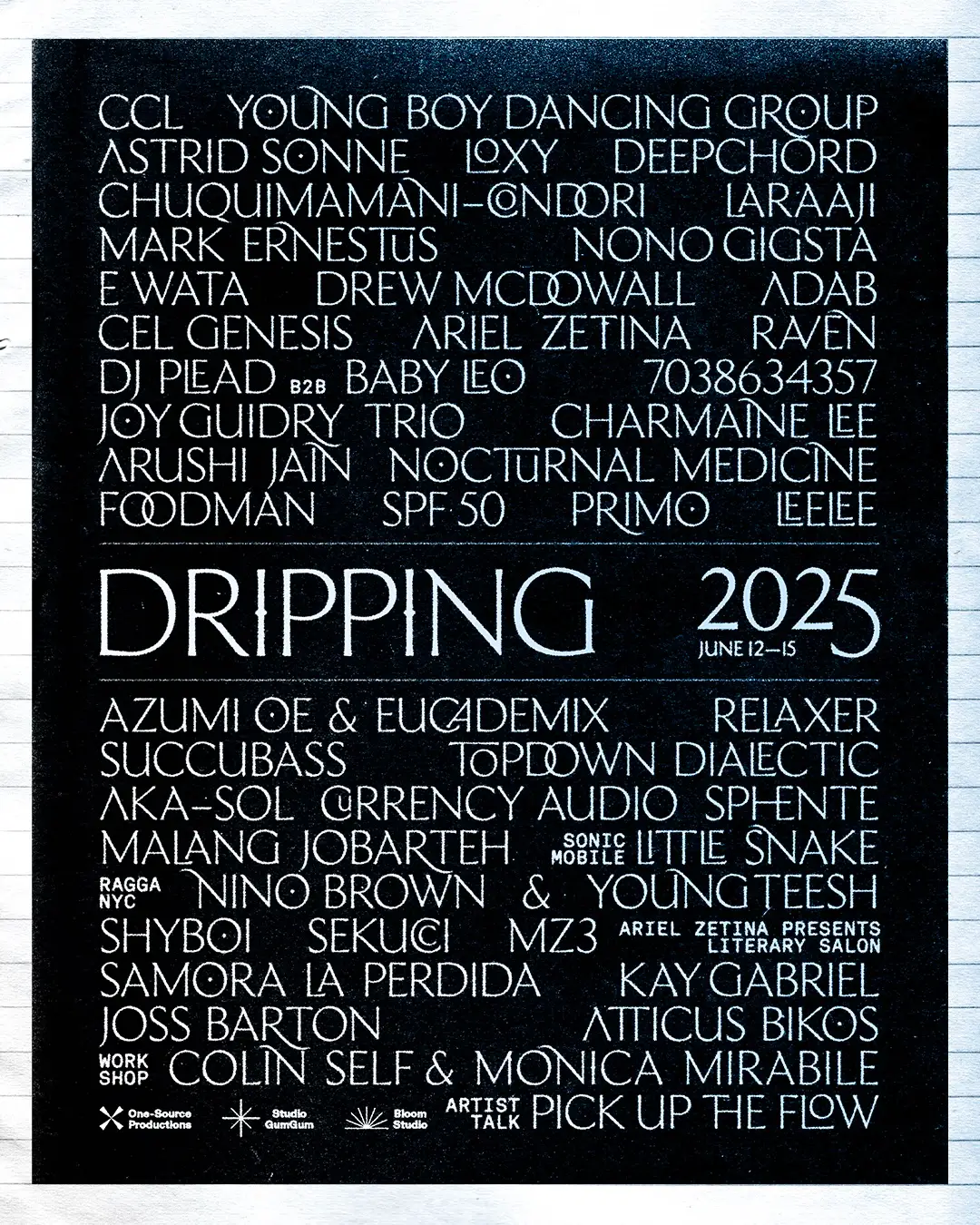

I bought my ticket as soon as the lineup was announced: it featured UK drum’n’bass legend Loxy, New Industrial drone maestro Drew McDowall, pioneering dub scientist Mark Ernestus, gabbercore bio-metal band Cel Genesis, wisp-techno haze vector Raven, and more, with many names new to me.

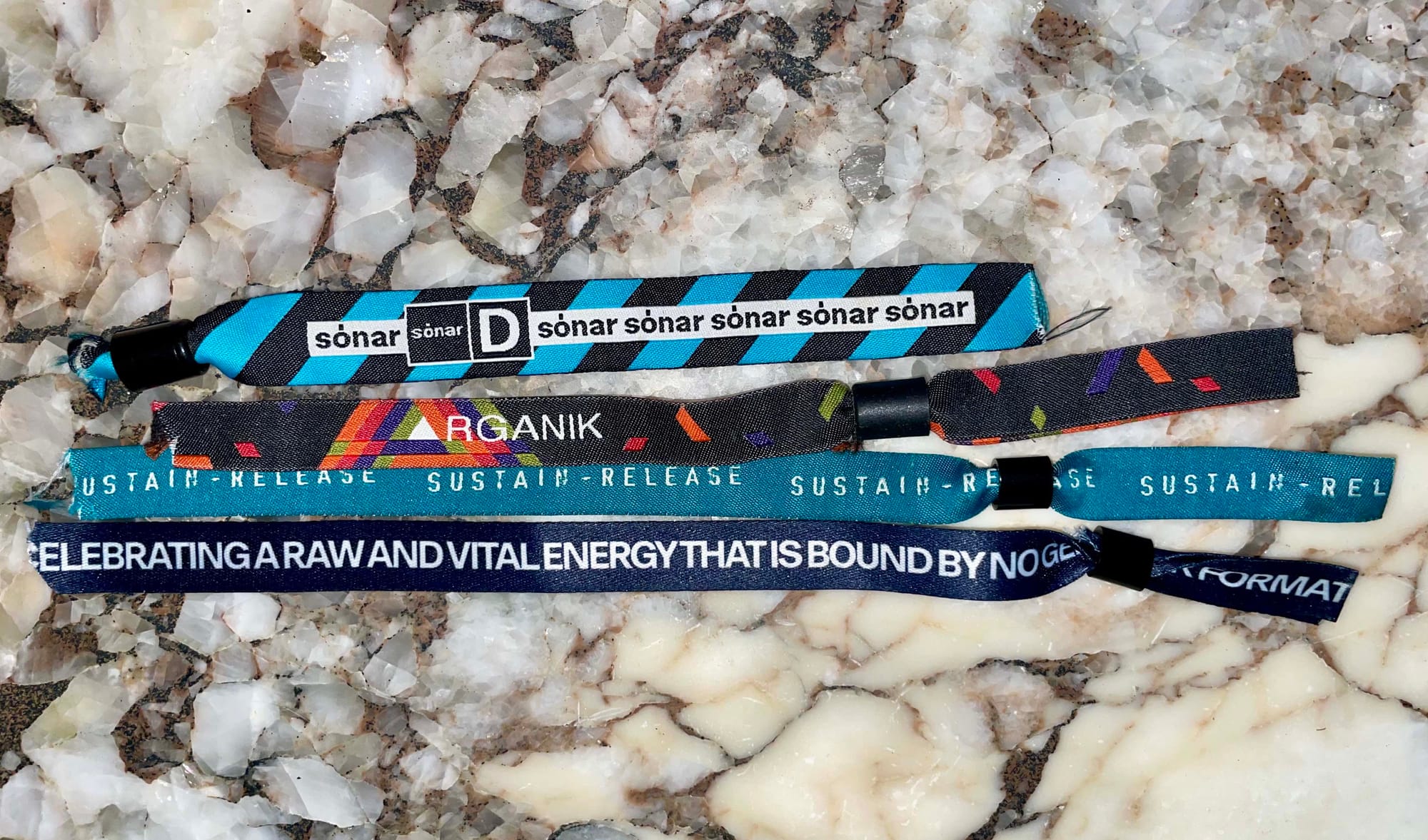

The array of sounds presented seemed chaotic at first glance, maybe. But I recognized commonality amongst all the artists on the lineup, and when we checked into the festival, the wristband I received read: CELEBRATING A RAW AND VITAL ENERGY THAT IS BOUND BY NO GENRE OR FORMAT. Really, I couldn’t have put it better myself—if I had to capture the mission statement of Thoughts of a Certain Sound in a single phrase, that would do it.

The venue, Camp Sacajawea, is a privately owned campsite in the northern reach of New Jersey. (The campsite, like all of New Jersey, occupies Lenape land; its name is testament to, and reflection of, America’s settler-colonial roots.) It’s large, beautiful, and richly green, thanks to East Coast summer rains. Upon arrival, I picked up our rented camping gear, and a crew of us pitched tents on a narrow southeastern corridor.

Proceedings kicked off on Thursday evening, one night earlier than previous iterations. After a Vietnamese dinner grilled on-site (“Dripping is delicious,” festival copy claims, and it’s absolutely true), we headed to a nearby meadow for Astrid Sonne, whose clarion voice, live cello and tender breakbeat-driven songwriting made the perfect festival opener. I missed Laraaji up next, because The Inn, the main indoor performance space, filled up within minutes—I realized immediately that capacity would be an ongoing negotiation throughout the weekend. Sphente, a New York-based gong artist, closed out the night on the Open Air stage outdoors. Immersive and shimmering, their performance was a personal highlight. Equipped only with a gong and maybe some FX pedals, Sphente was nonetheless all-encompassing and extraordinarily bodying at volume, a study in both minimalism and maximalism at once.

On Friday, things began to coalesce. The crowd gathered lakeside for swimming and shimmying to a DJ set from Aka-Sol, an NYC-based selector, who played three-ish hours of trip-hop, downtempo, and moody synth-forward drum'n'bass, the ideal afternoon appetizer. Later that night, after a spate of rain, I caught Midwest DJ Adab moving from amapiano into Missy Elliott in The Barn, the small (very small) dancefloor stage, before heading to The Inn, the main stage, for E Wata, a collaborative live performance between New York artists Enayet and K Wata. It was one of the finest expressions of half-time drum'n'bass I've ever heard: liquid-cooled sound design, drumless basslines, and near-total mastery of tension and release. Unfortunately, I caught only half the set—I had arrived a few minutes late, and had to leave once the room swelled to nearly uncomfortable capacity—but I was enraptured.

The rest of that night was blurry, but Nono Gigsta's jazz-drum tempo-shift train-ride DJ set, and the back-to-back percussion battle between festival co-founder Baby Leo and DJ Plead, kept me locked in a groove. Between these sets, led by a friend, I ventured outside for Nocturnal Medicine. I had no idea what I was in for.

What I got was part guided meditation, part kink scene, part seance, and part communal love-in. As I walked toward the open-air grove, I heard the throbbing and pulsing of a pitched-down edit of Nine Inch Nails' "Closer," and soon encountered Nocturnal Medicine: an MC, a DJ, two dancing ritualists, and a bonfire. Their performance was sensual, sexual, silly, and sincere, a beautifully earnest ode toward presence and connection manifested through word, sound, and movement. Throughout the performance, I felt slightly bewildered, not quite sure exactly what I was witnessing, as if a dream-state were bleeding into reality. That kind of experience was precisely what I came to the festival for, though I didn't know that going in.

On Saturday, the rain plan necessitated that Mark Ernestus, originally scheduled lakeside, play the Open Air stage instead. The switch-up was an absolute blessing in disguise: Ernestus's 4-hour DJ set, strictly 100% amapiano, on a stacked Funktion-One soundsystem, amidst a crowd of 700-something people outdoors, was genuinely one of the most exquisite dance communions I've ever participated in. I came late to amapiano, realizing its majesty only a few years ago. Outside, on a big system, the thick, percussive bassline grooves, melodic vocals, and sparse, precise production felt personally transformative—as though it had finally occurred to me, after all this time, what "bass music" truly meant. Mid-set, I turned to a friend and said, "If this were all I caught this weekend, the whole trip would have been worth it."

More was yet to come. My Saturday night began with the tail end of Bolivian-American artist Chiquimamani-Condori, aka Elysia Crampton or DJ E, whose work I've followed from afar, but don't know well. Their performance—samples; synthesizer and guitar; beats looping on CDJs; Latino rhythms and timbres colliding with disjointed noise and hip-hop tropes, a kind of pastiche LatinAméricana—captured, in sound, something quintessential I have long grappled with as a Colombian-American person but have never been able to fully express: the sense of being split between two cultures, never Latino enough to claim my Colombian-ness but certainly never at home with my American-ness, my whiteness, either. Witnessing Chiquimamani-Condori's queer Latino artistry, I began to weep, overwhelmed with awe, as they encapsulated, embraced, and embodied this double-bind wordlessly, not just through their music, but through their whole person. Then, not long after I arrived, the set was over, and I left in a daze, tears running down my face.

I took a minute to recompose myself and eat some food. Accordingly, I missed the European performance troupe Young Boy Dancing Group, which I had been told not to miss at any cost. (C'est la vie.) They were described to me variously as "feral," "intense," "bodily," and "sexual"; immediately after they finished, a friend in attendance said it was like "witnessing a C-section." Another friend was splashed with fluid from a bursting water balloon; we learned later it was lube. It seems their performance climaxed—forgive me, again!—with an anally-inserted laser pointer moment, which seems to be their hallmark.

That gave me time to head to the main stage, The Inn, for Cel Genesis, an Oakland band with extremely on-point design sensibility who blend doomy death metal with gabber and nightcore-esque anime-ish trance-melodics. Look, I confess: I have, on several occasions, chosen not to see them here in the Bay because I thought the combination of these sounds would be corny (and because their branding is too good). What an absolute fool I am, because—and there's simply no other way to put this—Cel Genesis fucking rips. Brutal, intense, severe, but also self-aware and catchy and just goofy enough, they put on one of my favorite shows of the weekend.

I spent the rest of the night in a swirl of cosmic introspection at the Open Air stage. Azumi OE opened with Butoh-inspired dance, writhing and unsettled, set to searing, uptempo live electronica by Eucademix (aka Yuka Honda, co-founder of Cibo Matto)—I was completely mesmerized from start to finish. Afterwards, Drew McDowall shuttled me off to innerspace; zoning into his cavernous drones outdoors, with softly swaying trees as a backdrop, was a delight. I took a break and missed 7038634357 (the artist's phone number, apparently), regrettably. I returned for Raven, a San Francisco artist with a prodigious discography of deep, murky techno. He played live for two hours, cutting up and reconfiguring bits of GNOSIS, his recent LP on Incienso, bringing the laid-horizontal crowd to their feet with oblong rhythms and interlocking harmonies. Last came Topdown Dialectic, an anonymous artist (remember those?—I’ll just say he's from San Francisco, too, though) whose live set, his first ever, cut angular shapes through deep swaths of dub and disembodied voices. Alas, after only half an hour, I succumbed to the siren song of a passed joint and it was time for me to retire.

I woke up to the throb of beats coming from Open Air, and I thought that Topdown Dialectic was still playing live, somehow. I wandered over and found CCL, the unsparingly flexible DJ, presently about five hours into their closing set. They rinsed out trance classics, jungle rhythms, and Joanna Law's "First Time Ever" acapella, Coldcut "Journeys By DJ" style—exactly right for the morning after. By 11 a.m., the weekend was a wrap.

What became apparent, after all was said and done, was how much thought, care, and intent went into programming and scheduling the festival: it's one thing to book a diverse lineup, but another to present it in such a way that audiences step outside their comfort zone. Throughout the weekend, live sets were sandwiched between DJ sets and vice versa; experiential dance performances were juxtaposed against the rave; syncopated drum-havoc against zone-out dronescapes; indoor against outdoor; and so on. In this sense, Dripping succeeded in a manner I'm not sure any other festival I've attended has. It's as if lines of demarcation between the experiences I had at the festival dissolved in a manner that mirrored the expansive curation of the lineup itself.

There is more I could write still: how exciting it was that Afro-Caribbean sounds, and Black artistry generally, were front and center. How refreshing it was that Techno-with-a-capital-T was barely present at all. How lovely it was to see people of all genders and sexualities commingling. How the lighting and sound were pristine. How I wish more DJ sets had been outdoors. And how there was room for improvement, particularly with regard to communication, logistics, and capacity management. (This year, the festival sold out for the first time; these issues are growing pains that will be smoothed out, I expect.)

Weeks later, I'm still thinking about my Dripping experience on the daily. Events like these remind me, with stark focus, that music is a communal and participatory artform. That collective ecstasy and generative discomfort are two sides of the same coin. And that despite it all, the musical experience—live and direct—still has the power to shock, delight, and unravel me. What more could I ask for?