HTRK's "Psychic 9-5 Club," eleven years later

Reminiscing on the Australian duo's third album, which influenced a generation of records to come.

There's a handful of records that have buried themselves so deep in my consciousness that I can barely imagine life without them. At a certain point, parts of myself began to osmose into these records, and in turn, the records into me—like Videodrome, but with headphones. Just over a decade ago, Psychic 9-5 Club, the pearlescent third album by Australian duo HTRK, wound itself deep into my psyche and never let go, singing a song I had always longed for but never knew I needed. Released in 2014 by Ghostly International and repressed in 2025 on its eleventh anniversary, its influence presaged a generation of records to come, mapping out a vision of soft-focus "post-ambient" music inspired by the club, but entirely separate from it.

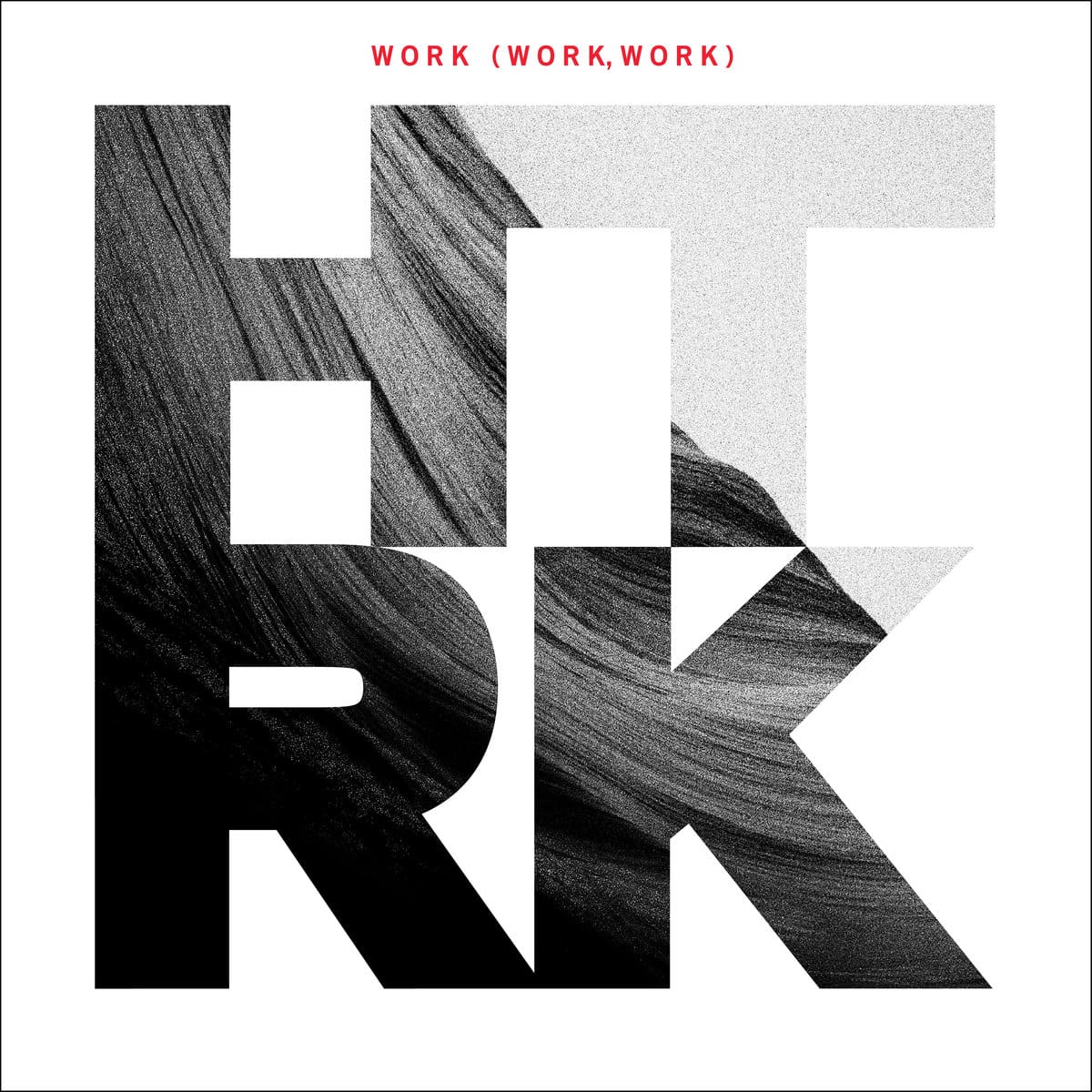

I first encountered HTRK when a friend insisted I listen to Work (Work, Work), the duo's dour, sharp, and soporifically groovy second album. Structured around spare TR-808 drum machine rhythms, the album scanned as electronic music to me, even though nearly every track featured aloof guitars and somber vocals. It seemed to borrow from industrial music and R&B in equal measure, an effect altogether unlike anything I had heard before. I was hooked as soon as I heard the record—not least because the cover, featuring little besides the band's logo, four textured letters stacked square, seared itself into memory at once.

I soon learned several things about HTRK in succession. One: their name is short for "Hate Rock," an acrid moniker I found at odds with the tender yearning core of their sound; I came to appreciate this dissonance as a reflection, in name, of the band's sonic contradictions. Two: the band, formed in 2003, were originally a trio ("Hate Rock Trio"); founding member Sean Stewart ended his own life in 2010. Three: the aforementioned logo was designed by Jonnine Standish, HTRK's vocalist; inspired by Robert Indiana's LOVE artwork, HTRK's riff is as iconic as its source material, cementing the band's visual design language as an essential component of their appeal.

In other words, by the time Psychic 9-5 Club was announced, I was well on my way to a full-fledged HTRK obsession. I knew I'd enjoy the record, but I couldn't have anticipated how much it would surprise me—and end up rewiring my own taste.

Listening to Psychic 9-5 Club, it's clear from the first that this iteration of HTRK is different from what came before. Instead of the terse, narcotic beats of Work (Work, Work), a cavernous thud announces the record, like the reverb tail of a rubber-coated anvil dropped into an abandoned well. Instead of prickly guitar, cascading synths bathe the ears in melancholy. And then Jonnine Standish, singer-songwriter, croons the most unforgettable opening lyrics I know:

This way

Oh, when you talk

You're talking more than your mouthful

—

This time

I'm gonna love you much better

I'm gonna love you much better

– HTRK, "Give It Up"

The mood had changed, and the sound had, too. There were reasons for this: first and foremost, Psychic 9-5 Club is the first album HTRK wrote entirely as a duo—Nigel Yang and Jonnine Standish—following the death of Sean Stewart. In a 2019 interview with The Quietus, Standish recounts: "When we toured Work (Work, Work), there was a real heaviness to it … We've had a lot of drama in our lives. Psychic 9-5 Club was always trying to release some baggage, stuff that had really taken its toll on us." And they had decamped from greyscale Berlin to sunny Sydney, in their native Australia, which had more of an effect on their music than they might have realized: "Coming to Sydney [from Berlin] was kind of like how you'd feel if you were Russian and went to Cuba," said Yang, in a 2014 interview with Dazed. "It was quite fascinating to witness how it was really affecting the kind of music I was coming up with."

The rest of the album proceeds apace. Standish's voice glimmers throughout, approaching, at times, the tenor of Sade. The production, stripped down to the studs and awash in dub technique, showcases arrestingly simple grooves. There is nary a guitar to be found, and the drums are submerged and wispy but closer than they appear in the mirror, paradoxically. The band's tender yearning core is ever present, but the trappings are more intimate, more sensual, and more self-assured. It sounds like a whisper, a close hug, a soft caress.

At first, I understood Psychic 9-5 Club as an "ambient" record, insofar as mental models of genre were concerned. Which, in many ways, it is: it's soothing, atmospheric music, eliciting a certain mood. It shares a great deal, in terms of timbre and dynamics, with the "ambient music" I grew up on: Tetsu Inoue, Pete Namlook, Robert Rich—artists inspired by the Berlin School tradition, to be very loose with it. But Psychic 9-5 Club is a collection of songs, not tracks. Drifting and subdued songs, yes, but vocal-driven songs with four-minute runtime, still. HTRK has forebears in this tradition too, of course: Cocteau Twins, Slowdive, Low—to name a few. Eventually, I began to conceive the album as something else altogether.

When the record came out, I was in my peak club era. I was going out two or three nights per week—sometimes DJing, sometimes dancing, sometimes producing the club night myself. I'd come home in the wee hours of the morning, collapse on the couch, and, with frequency, choose HTRK to soundtrack my comedown. Chromatic and compassionate, Psychic 9-5 Club was the perfect afterhours companion.

At some point, it dawned on me that Psychic 9-5 Club was a pop record made by artists who live and breathe electronic music—made for listeners who do the same. (I use "pop" glibly here; it's not like HTRK and Ariana Grande have much in common.) It wasn't club music at all, but it was somehow of the club.

In the years following the album's release, techno music, and club culture writ large, exploded in popularity to degrees I never imagined possible—not in North America, at least. Berghain, Berlin's queer club institution, became metonymic shorthand for a newly public embrace of liberated hedonism; media outlets, even the most staid and institutional, stumbled over themselves in a rush to publish "how to get into Berghain" articles. Conan O'Brien filmed a segment outside the club. (He didn't get in.) "Ketamine therapy" went viral, becoming a quasi-legal million-dollar industry overnight. And now, in 2025, The Guardian's Song of the Year was Spanish pop princess Rosalía's "Berghain"—which features Björk and Yves Tumor, because of course it does.

Psychic 9-5 Club had nothing to do with any of this, of course. But like many great pieces of art, it happened to land in the right place at the right time. Eleven years on, its influence, whether subtle or overt, is felt far and wide. It's hard to imagine French chanteuse Oklou, whose crystalline downbeat synthpop was 2025's most exciting mainstream breakthrough, without the foundation laid by HTRK. Or her pop-ambient countrywoman Malibu—or, for that matter, Bladee, the Drain Gang ringleader who worked with Malibu and Oklou alike. Or James K, the New York City artist currently inducting an entire generation of new listeners into the nascent trip-hop resurgence. Speaking of which—HTRK's hometown, Melbourne–Naarm, has undeniably become the global nexus point of contemporary trip-hop; the duo's influence is written all over the region's thrilling new sounds: Hysterical Love Project, Dregs, a.s.o., and so on.

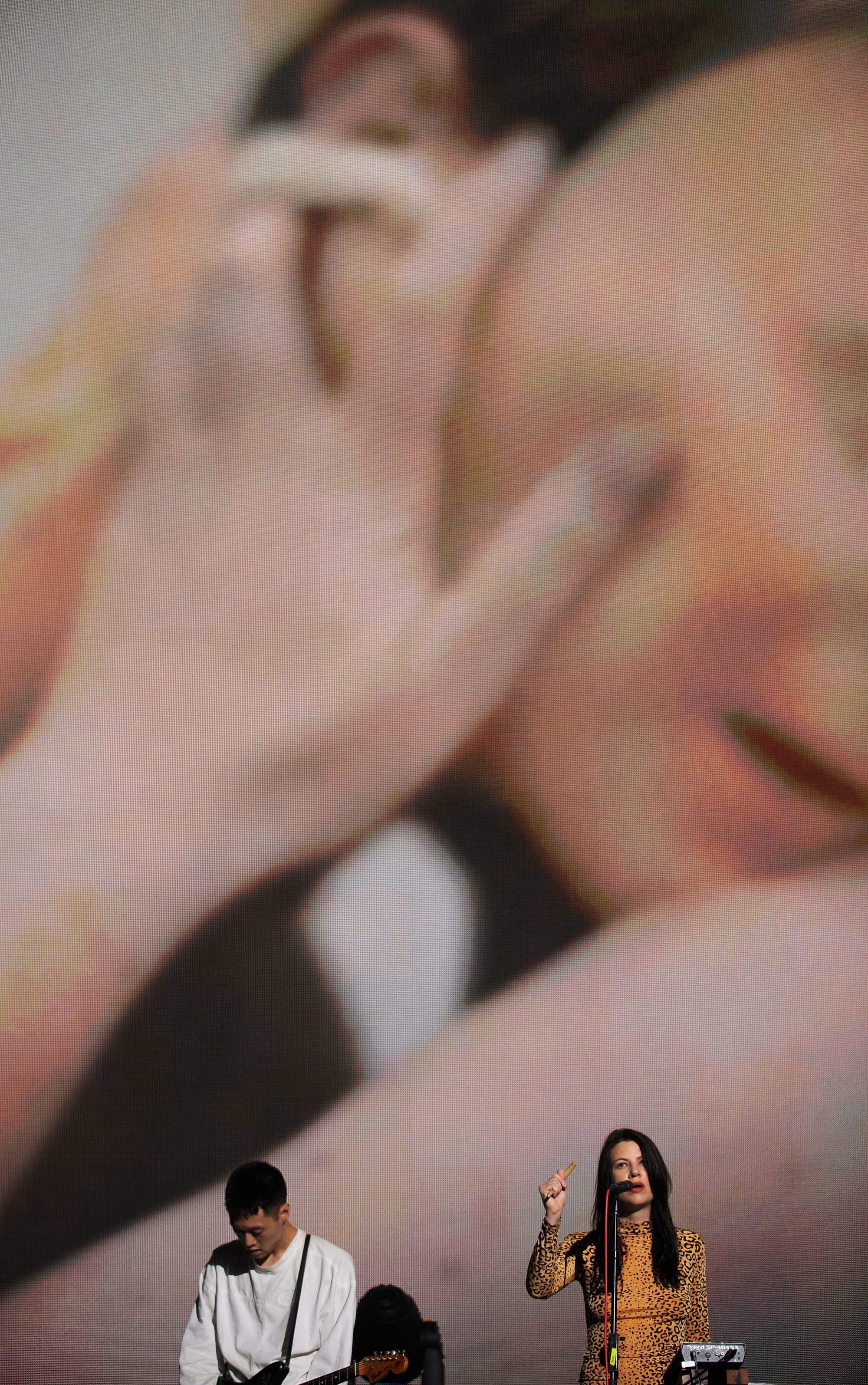

In April 2025, HTRK returned to New York City for an in-person pop-up, envisioning the "Psychic 9-5 Club" as a physical space you could visit. They enlisted various friends, collaborators, and like-minded artists for DJ sets and performances: Deep Creep, Downstairs J, Jezmo, Bookworms, Zebrablood, Kim Ann Foxman, Adrian Rew, Tove, and James K. Though I didn't have the chance to attend myself, I admired the concept from afar as both remembrance and realization.

This year, too, HTRK quietly and unceremoniously marked some 21-ish years together as a band. Few artists manage such longevity. Fewer still produce work of this caliber. Each time I listen to Psychic 9-5 Club, I feel like I'm sinking, on demand, into a dream I once had and have always hoped to return to. May we all find such stewards in our lifetime.