Longform: The New Industrial

Or why Dean Blunt might be the truest spiritual successor to Throbbing Gristle.

I've been following the thread of experimental and unconventional music for nearly thirty years now, and over the past decade, I've noticed something I haven't quite been able to put my finger on. It's not necessarily a scene or a movement, not in the ways we usually apply those words to music-world phenomena. Instead it's perhaps a tendency or a throughline—or, bear with me, a coalescence—in which strands of seemingly-disconnected left-field musical forms and styles have increasingly woven closer together: clustering, communicating, butting up against each other.

I'm calling this configuration the New Industrial—insofar as it shares some of the sound and stylization of "traditional" industrial music, which for the purposes of this essay I'll refer to as the Old Industrial, but is differentiated in scope, aesthetics, and approach. Whereas the Old Industrial predominantly concerned itself with shocking or even horrifying imagery and sound, often deployed with a wink and a nod, the New Industrial is instead situated around concealment, deception, and mystery—a kind of digital-age hermeticism that, in today's hyper-connected, always-online world, feels genuinely transgressive.

The Old Industrial—and the changing of the times

Industrial music is named after Industrial Records, the record label founded in 1976 by British musical aggressors Throbbing Gristle. Monte Cazazza (1949-2023), a debauched performance artist who spent most of his life in San Francisco, coined the slogan that gave the genre its moniker: Industrial music for industrial people.

Evolved from the confrontational performance art collective COUM Transmissions—which was founded with Dadaist intent by T.G. member Genesis P-Orridge in 1969—Throbbing Gristle, and COUM before them, reveled in terrorizing audiences with disturbing, challenging, and revolting imagery, including pornography, violence, and fascist symbolism, all deployed with a particularly retrograde ironic sensibility.

The music was lurid, weird, and unsettling to match—but also groovy, playful, and not infrequently beautiful. Since then, "industrial music" has become a cipher of sorts: a vaporous, ill-defined term deployed most often to describe music that is abrasive, antagonistic, is not for the faint of heart, and probably has clanging sounds.

At the root of this scene's brutal aesthetics lay a pseudo-ironic "are they serious or aren't they?" pose, which landed very differently back in the '80s and '90s—after the fall of the Berlin Wall, but before 9/11—when it seemed, at least amongst those highly educated Western elites who codified "neoliberalism" into a political philosophy, that "the end of history" had finally arrived. In the ascendant age of cable news and national newspapers, when information traveled no faster than dialup modems could muster, the rub-your-face-in-it provocations of industrial artists made a demented sort of sense.

But suffice it to say that in the 50-ish years since Throbbing Gristle first scandalized crowds of Thatcherite Britons, culture has shifted. Global politics have turned deeply, darkly rightward. "Edgelord" has entered the everyday vernacular—out of necessity. And the West is collectively suffering from a code-red case of information overload, in which a never-ending onslaught of data, including any number of horrors beyond comprehension, are pumped directly into the obsidian rectangles we gaze into every minute of every day. Viewed from a contemporary lens, much of Old Industrial's shock-and-awe schtick seems puerile, at best, or toxic and outright harmful at worst.

In the early 2010s, tides began turning. For but one example: In 2013, veteran U.K. experimental musician William Bennett—whose project Whitehouse was foundational to the industrial mythos but was also notoriously vile, ludicrously extreme, and brutally misogynist—published a flaccid apologia in response to what today would be known as a "cancellation attempt." Bennett wrote then: "[The aesthetics of Whitehouse weren't] supposed to be taken seriously and, looking back, it was stupid of me to think that [they] wouldn't [be] when taken out of context. My bad."

Not long after, a writer named Josh Hall published a takedown of Bennett's work. Hall’s essay isn't a rhetorical masterpiece; several of his arguments were imprecise, even sloppy, but it was clear that they were indicative of something epochal shifting in culture at large: "You can’t unquestioningly use … the imagery and language of colonialism and misogyny, and then act aghast … that you might be propagating colonialism and misogyny."

Some ultimately took their previous deeds to task, like legendary musician and audio engineer Steve Albini (1962-2024)—who wasn't an industrial musician per se, but was intimately connected to the culture and several core artists: "A lot of things I said … are clearly awful and I regret them. For myself and many of my peers, we miscalculated. We thought … we were not harming anything with contrarianism, shock, sarcasm, or irony. [We] were trying to [highlight] … the everyday nonchalance [toward] the atrocious, all while laboring under the tacit mistaken notion that things were getting better."

Today, "my bad," to borrow the phrase, no longer cuts it. Having it both ways—the privilege of not being taken seriously—no longer comes with such ease. Times have changed.

The New Industrial: an assemblage of sounds

Just as it became ever more difficult to justify extreme aesthetics either artistically or politically, a new wave of left-field musicians began exploring esoteric, recondite, and dark themes in their own way—referencing Old Industrial music obliquely and tacitly.

To be clear, the relationship between "Old" and "New" Industrial that I propose here is neither causal nor linear. Like most developments in musical form and style, it occurred over a period of time, in an erratic back-and-forth fashion, and without any explicit overarching narrative.

To go one step further: both Old and New Industrial, as I characterize them, are less musical genres and more musical heuristics. In other words, both are organized less around common sounds and more often around thematic, stylistic, and/or philosophical approaches. In practice, this means defining what industrial music "is" or "isn't" is inherently fuzzy. But this fuzziness is a feature, not a bug, and is one of the primary reasons that industrial music has persisted as a style, sound, and approach for nearly half a century.

Lastly, I have no doubt that many of the artists and labels I select as exemplars might consider the entire notion of "New Industrial" silly—or just flat-out wrong. Nonetheless, this framework has helped me illuminate and understand the connections between this diverse, ever-growing network of musicians and artists, and so I share it with that spirit in mind.

The New Industrial core (there is no core)

HYPE WILLIAMS: DEAN BLUNT + INGA COPELAND (London, U.K.)

There is no archetype for the New Industrial—but if I had to pick one, I'd choose Hype Williams, the short-lived duo project from experimental artists Dean Blunt and Inga Copeland, who now uses the alias Lolina. (Neither are the artists' real names, naturally; the mystery is the message.)

Founded sometime around 2008—one year after the release of the first iPhone, pointedly—Hype Williams sounds like being online feels, sort of. There's much more going on than that, but in the chaos and disjointedness of their music, Blunt and Copeland mirrored the scattered, hyperlinked, and decontextualized schizoid logic that has become endemic to present-day digital culture.

Hype Williams eventually ceased to be; both artists went on to solo careers producing post-conceptual music and art. Blunt, in particular, has attained mainstream-ish success, despite refusing, at every turn, to provide the all-access-granted personal-brand storytelling that the algorithm demands from those wishing to participate in the modern music industry.

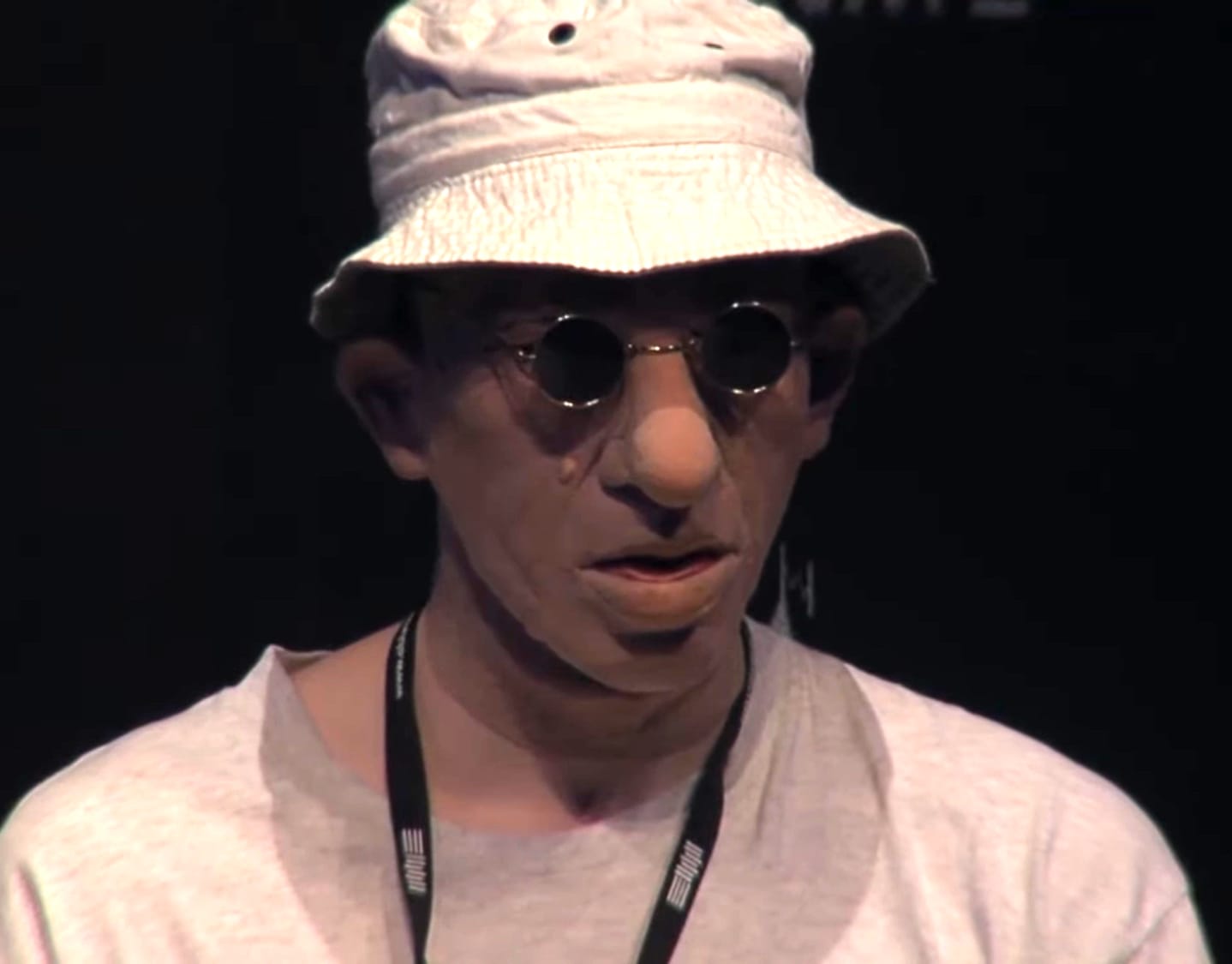

Recently, a video panel interview from 2011 resurfaced on YouTube, ostensibly about "the future of electronic music," featuring six people, including Blunt, vocalist and producer Maria Minerva, and several journalists. Blunt introduces himself as "Glenn Danzig, lead singer of the band called Misfits"—one of his most common misdirections. As far as interviews go, it's pretty good—everyone, including Blunt, engages sincerely. But the mood overall is bizarrely, even nightmarishly surreal: Sitting directly to Blunt's left is a person wearing a bucket hat, tiny pitch-black Windsor sunglasses, a promotional t-shirt from the 1999 Disney film Tarzan, half-on Timberlands, and, deliriously, what appears to be a full head mask; this person is never introduced, spends most of the interview glaring downwards with their mouth hanging open, and never utters a single word. Nobody comments on the presence of the nameless, speechless masked person, and the whole thing feels more like a snippet of a David Lynch film than music journalism.

Is it art? Is it comedy? Is it horror? Maybe all of the above, or none. Remarkably, though, this stunt doesn't really feel like "trolling," at least not in the 4chan sense. Blunt's (and Hype Williams') public-facing absurdities seem designed to unsettle, confuse, and/or disturb, but not to bully or deride. This aligns Blunt and his cohort spiritually with Throbbing Gristle—and the Old Industrial—though their provocations are inverted: they are covert acts of bewilderment or withdrawal, rather than overt acts of shock or atrocity.

For Blunt and Copeland—and for New Industrial writ large—"no" is the new "yes."

BLACKEST EVER BLACK + LOW COMPANY (London, U.K.)

Launched in 2010 with a series of EPs by Raime and Birmingham techno legend Regis (better understood as an industrial artist himself), the record label Blackest Ever Black's highlights include the gloomy, gaze-y post-goth of L.A.'s Tropic of Cancer; corroded, noisy dub from Bristol's Ossia; crystalline braindance from Edinburgh's Dalhous; spectral singer-songwriter guitar-synth from Melbourne's Carla del Forno; and so much more.

During their heyday, the diversity of Blackest Ever Black's offerings didn't quite seem to fit together. Traditionally speaking, record labels were usually organized around specific sounds or genres—Blackest Ever Black, though, put out icy club bangers, discordant walls of sound, and moody whispers of intimacy one after the other. The rise of streaming—which simultaneously rendered musical genres less relevant than ever and led to subcultures themselves fracturing, dissolving, and reincorporating—partially explains the breadth of the label's offerings. But in hindsight, by presenting these sounds together, without explanation, the label was creating a new kind of connective tissue.

Blackest Ever Black shuttered in 2019, and was followed by a record store with an in-house label, Low Company, which put out twisted tech-step drum'n'bass (Pessimist) beside lo-fi post-punk (Bobby Would) beside wistful, mystical moon-lit folk (Brannten Schnüre), and so on. And then just like that, Low Company was done, too.

Mysterious, inscrutable, endlessly compelling, stylistically diverse: the New Industrial, and these record labels, in a nutshell.

JOHN T. GAST (London … maybe? U.K.)

It took me a decade to figure this out, but say "John T. Gast" quickly enough and you'll realize it's a pun—"jaunty gast," which might translate from the chiefly-British as "friendly scare." That seems as good a description of his music as any, which veers from mischievous, to ominous, to intensely rhythmic, to heartrendingly beautiful—sometimes all on the same record.

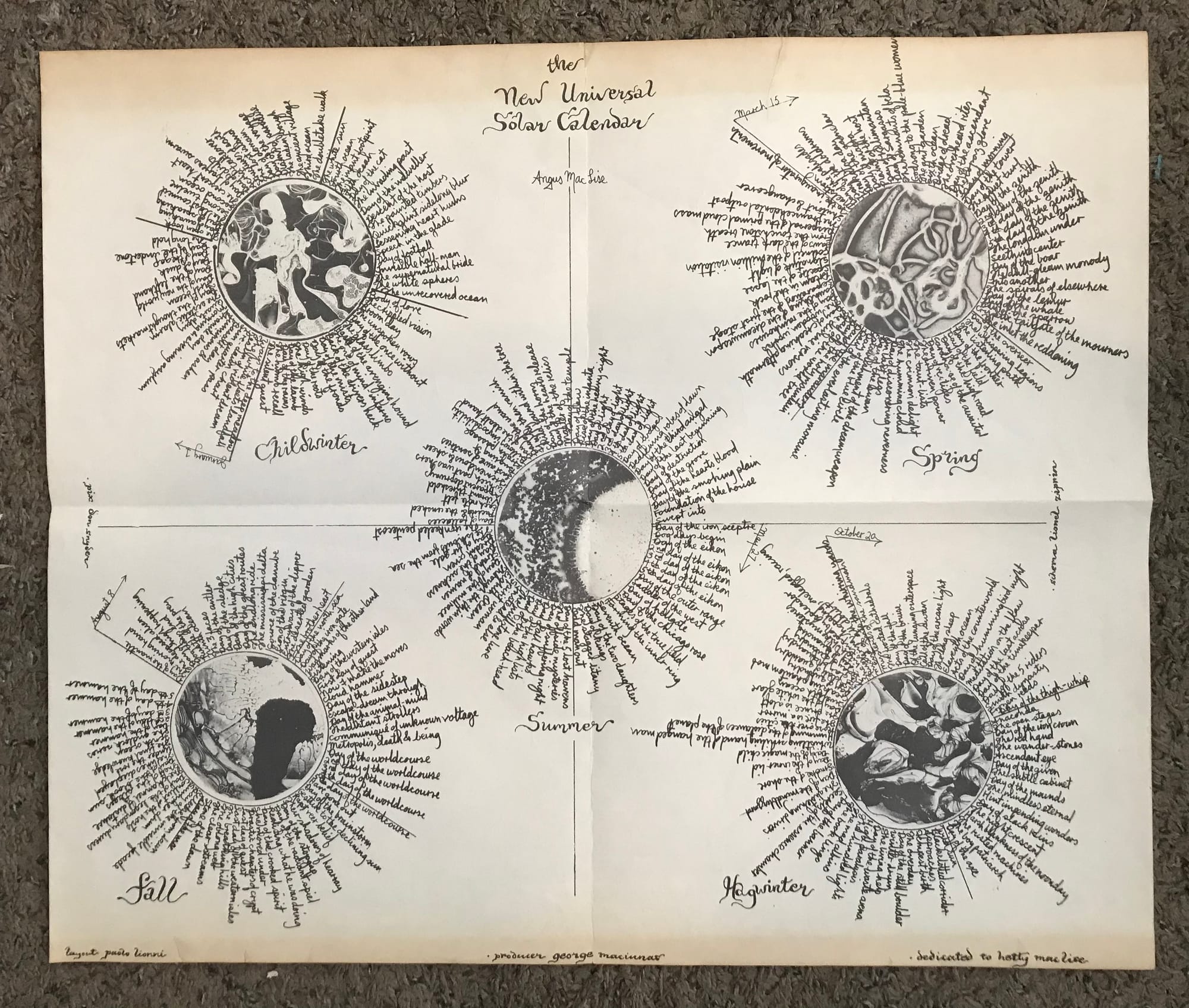

Gast plays with genre like a jester—his discography is a font of exquisite weirdness. There's baroque Anglian piccolo-hop (Young Druid); haunted cosmic ambience (wygdn); breathtakingly tender harpsichord (Garden of Love, with Serafina Steer); and numerous heavyweight club tracks, like "Overseer," a ten-minute long ritual dance incantation on a single-sided 12", which samples occult American artist Angus MacLise's spoken word poem, Universal Solar Calendar.

The sigils connect: Old Industrial legends and queer sorcerers Coil were deeply inspired by MacLise, frequently recasting his poetry into their own work.

Gast is also an inveterate collaborator, appearing on at least two Dean Blunt records and several EPs with Inga Copeland, among many others. Under the alias Gossiwor, together with MC Boli, aka Asger Hartvig, a Danish instrumentalist loosely connected to Posh Isolation, the pair released a full-length LP, Lighthouse. It’s one of the most starkly beautiful and subtly terrifying records of the modern era, conjoining neoclassical composition with doomed electronics.

And even though Gast's music may be abstruse and arcane, it is definitely not unfriendly or contentious. That's what makes his work, and New Industrial music, so powerful: it beckons the listener in, but reveals nothing.

In a world suffocated by profusion, it is a welcome reminder, as ever, that less is more.

The second volume of this essay, a roundup of New Industrial artists and record labels, is available here: Now Listening: A New Industrial Roundup.

Sincere gratitude to Nicole Devillers, Shawn O'Sullivan, Nihar Bhatt, and Jason Polastri for their editing assistance, feedback, and guidance.