Look Back: A Ghost in the Machine (an Autechre feature from 2015)

A nearly 10-year old feature on Autechre—with the complete interview transcript to follow.

During my time at SF Weekly, when I was writing the weekly column that this newsletter-blog-zine is named after, the editors would sometimes approach me with one-off story opportunities they thought I'd be a fit for. One of those opportunities was an interview with British electronic music pioneers Autechre, in advance of their 2015 U.S. tour, which, as of this writing, remains the last time they performed live in North America.

I discovered Autechre's music when I was barely a teenager, the consequence of spending far too much time feverishly downloading MP3s from IRC channels, on a 28.8Kbps dialup modem, at a tender young age. Their music permanently altered my consciousness. I was thrilled to be able to speak with them.

We spoke for nearly two and a half hours—the pair were extraordinarily down-to-earth, friendly, easy to talk to, and absolutely game to answer all of my fanboy-ish questions. In my 20-something year career as a music writer, this remains one of my favorite interviews I've ever done.

But because I was writing a story for a free newsweekly with a generalist audience—designed to promote their October 2015 S.F. show, at the now-shuttered downtown club Mezzanine (RIP)—99% of the interview went unused and was never published.

I'm republishing this story for three reasons:

- SF Weekly is now a zombie publication, a literal shell of its former self, bought for pennies on the dollar by an East Bay real estate investor; dozens of my original stories for the former newsweekly remain published on its website, including this one, but my bylines have been scrubbed—or worse, re-attributed to fake authors. By republishing this story on my own platform, I am reclaiming my own work—and raising a middle finger, if impotently so, at the investor-class vultures whose extractive vampire capitalism led to this outcome.

- This Autechre story is an interesting time capsule, depicting an inflection point in electronic music in America, published just as big-business "EDM" schlock was beginning to reach its market saturation point, but several years before Boiler Room and video-recorded Instagram-ready DJ sets would capture the culture completely. Plus, it's nice to look back at old work and see that my writing has improved since then, especially at the sentence level. Maybe.

- I mentioned that 99% of the interview went unpublished. Across the next two weeks, I'm going to publish the complete interview transcript—all 8,200 words of it—for the first time, with Rob and Sean's permission. It's a delight to read, featuring insights on their music writing process, their relationship with one another, and anecdotes about Coil, Nine Inch Nails, Meat Beat Manifesto, and more. The complete transcript will be available for paid subscribers only. If you've been on the fence about subscribing—now's a good time!

It is a common criticism in America—especially among the traditional rock'n'roll set—that electronic music lacks soul. Programming a machine will never match the fluidity and grace of playing an instrument; the rigor of hardware cannot convey genuine pathos, or so critics say. It's a pervasive notion: Shellac's Steve Albini recently told abrasive techno producer Powell, “I've always detested mechanized dance music, its stupid simplicity, the clubs where it was played, the people who went to these clubs, the drugs they took … basically: 100 percent hated every scrap.”

Endless counter-examples skewer this breed of willful ignorance — the gospel roots of Chicago house music or the sci-fi futurist dreams of Black emancipation in Detroit techno, for example—but Autechre's music is something else entirely: it is not just music made by machines, but it is music of machines, something truly unique that exists without parallel in the “acoustic world” (in other words, the realm of purely non-electronic music). On Friday, Oct. 16 [2015], the duo [brought] their decades of experience to San Francisco, returning to the Mezzanine for a special Treasure Island Music Festival night show.

Sean Booth and Rob Brown released Cavity Job, the first Autechre record, in 1991, but that wasn't their first time teaming up: the two Brits released a record together in 1987 under the name Lego Feet, full of playful, simple rhythms that prefigured the first couple Autechre albums. Cavity Job is an oddity when compared with the rest of Autechre's discography, and it's also a rarity, essentially impossible to find until 2011, when it was digitally reissued in a compilation of the duo's EPs. But as a historical document, it is telling: its artwork, especially the enormous Autechre logo in a typical graffiti typeface, reflects the pair's roots in hip-hop and electro (think Afrika Bambaataa, Mantronix, and Man Parrish). And the sound it contains, full of pumped-up breakbeats and big synths, is a textbook example of late-'80s U.K. breakbeat hardcore, the kind of music the pair were raving to.

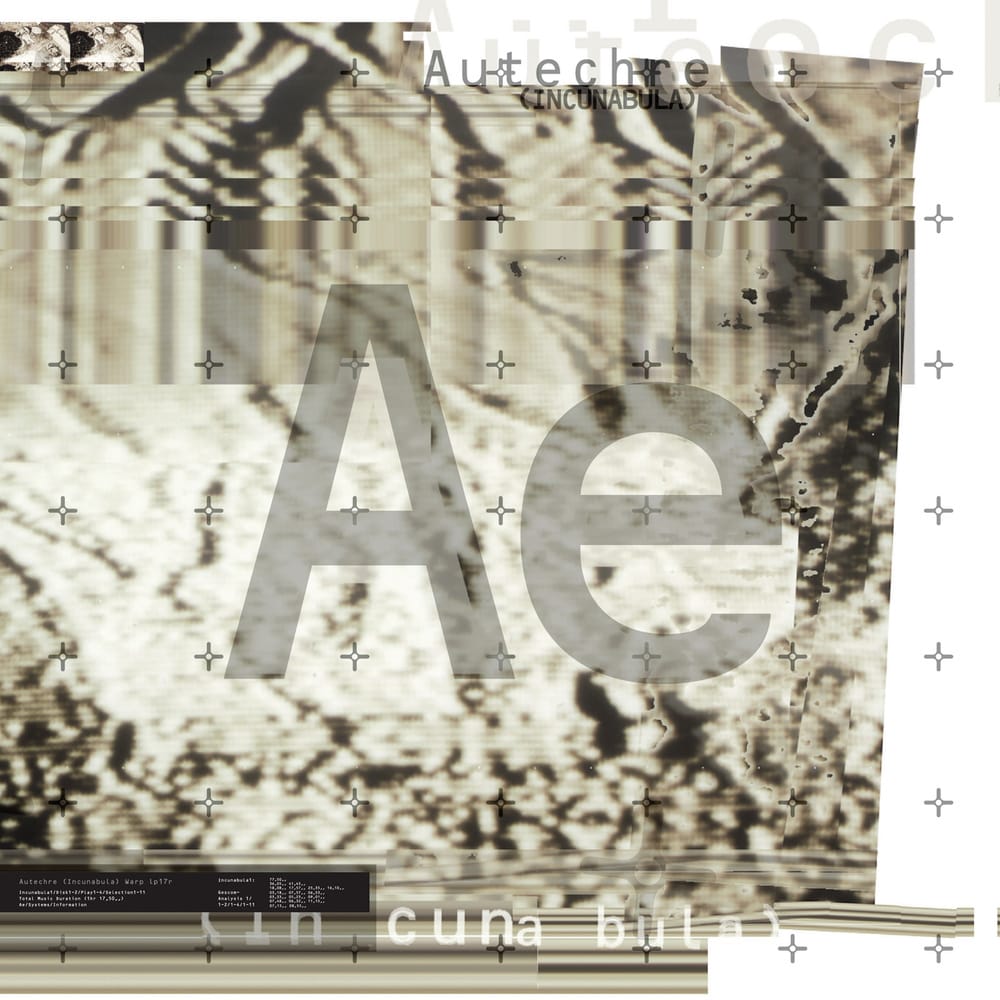

Two years later, the first full-length Autechre album was released with the fitting title Incunabula. “Incunabula” is a Latin term used to describe printed matter created before 1501 A.D.; more generally, it refers to foundational or source works of any kind. And so began the duo's long forward trajectory toward electronic music's vanguard, a position they have maintained ever since.

Autechre has long had a not-entirely-undeserved reputation as producers of “difficult music.” “What we do at times comes across as self-indulgent, and that can be used as a negative criticism,” allows Booth. “I don't want to patronize the audience. I don't like the idea of someone making music that has a broad appeal by intentionally leaving out elements that might confuse the audience or whatever. We kind of do the opposite of that. We try to make music for someone—for us—that will push ourselves as far as we can.”

With the assistance of some notable contemporaries such as Aphex Twin, Black Dog Productions (later known as Plaid), The Orb, and others, Autechre ushered in a new era of “electronic listening music” that eventually came to be known as “intelligent dance music,” or IDM. This controversial (for obvious reasons) moniker, adopted worldwide, was coined here in the Bay Area, then spread far and wide by O.G. techie Brian Behlendorf and his website Hyperreal, a critical linchpin for connecting the disparate bits and pieces of the early Bay Area rave scene. Booth, however, describes those early days more ambiguously: “I think our scene is sort of written up as being, you know, kids who were into dance music B-sides or chillout music that wasn't for the dancefloor, or some other sappy sounding phrase. But really, it was people who weren't genre-specific who were the big influence on our sound. People who weren't genre-specific—you didn't really know what they were doing. Was it house? Was it rave music? Was it electro? It was somehow all of these things.”

While pushing boundaries has always been Autechre's modus operandi, not all of its output presents a challenge for the ears. The duo's early work (Incunabula and Amber, in particular) reads as downright easy listening compared to the hyperkinetic, dense work they produce today. But in their time—just over 20 years ago—these works were revolutionary, built from carefully sequenced beats and brooding, spine-tingling washes of synth. By emphasizing the cerebral and the melancholy, Autechre stood in stark contrast to the majority of electronic music produced contemporaneously, which was engineered for dancefloors—music for the body, not the head.

By the latter part of the '90s, Autechre began to step off the proverbial deep end. Chiastic Slide, the duo's fourth record, was a sea change—not just for Autechre, but for electronic music as a whole. Perhaps more so than any other record that came before it, Chiastic Slide captured the music of machinery itself, seemingly coming from another world where robots are the native form of life, in which they stumble across human music and do their best to recreate it. It marked the beginning of a gradual shift in Autechre's music, away from the organic, natural, and compositional toward the stochastic, chaotic, and programmatic.

Each record that came after Chiastic Slide saw the duo's music become more and more intentionally disarrayed—the result of a move away from hardware and towards software, particularly Cycling '74's Max, a “visual programming language for media,” that allows for the manipulation of audio and visuals, with an endless number of applications. Autechre use Max as a kind of framework or platform, designing bits of software within the software; these days, their music-writing process happens in two parts: writing software during the day, and creating music with it at night. At this point, Max is as integral to Autechre's music as Booth and Brown are; according to Booth, “with a lot of our [music writing process] being algorithmic, it's getting to the point where it's difficult to say what's composition and what's algorithmic, when you define the algorithms that tightly, and we enjoy that grey area.”

Booth and Brown have been living and working long-distance for 20 years, but Max helps them bridge that gap. The pair have a mutual feedback process where they send their own patches and systems to each other for tinkering, and—most of the time—total reconstruction.

“Sean will be building widespread systematic changes, and I'll just be toying with them all day as instruments, as recorders, as sequencers,” says Brown. “You get this testing cycle going on. We're trying to one-up each other. It's B-boy culture, trying to outdo each other, applied to making music.” It's a friendly battle, says Brown: “Sean and I, we'll compete. We won't bite each other. I'll try rebuilding [one of his Max patches] from the ground up, my way. And that will have its own consequences, and it helps—with the musical output. It's a really good way of keeping things on the boil, keeping things a little bit uncomfortable. It keeps us interested.”

This playful back-and-forth, two old friends trying to outdo one another, is the driving spirit that has kept Autechre going for so long. The pair, according to Booth, are “very competitive, internally, but really, we're seeking approval from each other. Two sides of the same coin, isn't it? There's no one I want to impress as much as Rob.”