Words With: James Whipple (Hesaitix, M.E.S.H.)

Musical hiatuses, production flow, artistic growth, connecting with listeners, doing your own thing.

His tracks were nervous and kinetic, unmoored and unshackled from rhythmic constraints. He co-produced a Berlin club night, Janus, that counted Total Freedom (now Bobby Beethoven), Arca, Chino Amobi, DJ Marfox, Elysia Crampton, and Rabit among its guests and collaborators. "Futuristic club music," in other words, as he describes below.

After two lauded LPs for Berlin post-everything label and institution PAN, he seemed to go quiet. But in December 2024, he released a new LP, seven years after his last, under a new alias, Hesaitix.

Intrigued by his hiatus and his extraordinary new record, I caught up with James in the middle of December. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

on breaking and returning

When I think of 2020 to 2023-2024, it's like, I have to go into my photos app to see what I was actually doing.

I was kind of hitting my stride being a "self-employed independent music guy" around 2018-2019. And then 2020 happened. I got stuck in Ojai during COVID, because I came out here just for a three-week visit, in March, right before it all went down. And then I had a major medical issue, so I was actually in California for eight months. But, yeah, I was hitting my stride in my little niche electronica thing. And then for two years—all of that was shut down. Before lockdown, I was making a very modest living by touring. And then every once in a while, someone would ask me to do some project here or there. And then suddenly, after lockdown, it's like I'm teaching here, I'm working for this agency there—I was doing so many different things for these one-off little pieces of income, and that was completely exhausting. So I had gotten totally out of music, and in 2021-2022, I didn't want to just jump straight back in and release an EP and get back into the game in that way, because I wasn't really inspired, right? So [my break from music] was a very necessary step.

For me, it was like I was so in my own world with my own influences and things I listened to before I started releasing records and had a platform, and then the transition to—suddenly being in this mix of what's happening now, what was going on month to month—I was in the discourse, but I just didn't necessarily feel like I was meant to be there. So with this new record, it's really a little bit nostalgic. It still, of course, has my stamp on it. It's also kind of reflecting on the music that I was listening to when I was 17, so about 20 years ago. And you know, back then, I didn't want to be in the conversation. I'm just really picky about what I listen to, so I can't be in it, week to week, "what's new," that kind of thing.

I think that's why as a DJ, I was never gonna really be full time with that—because when I get promos, I'll find something that I'm really obsessed with. Then I'll play it for three or four years, and I'll start getting embarrassed that I play this one person's track every single time I'm playing out, no matter the context. I'll have a friend who's just making tons of incredible tracks, and I'll be like, Okay, I can't play three of his tracks [in one set], right? Or can I?

I just was never able to become that kind of guy that's like, always finding new music and digging. I just have my obsessions, and I've embraced that more. And I've been focused on my own music again, and I'm not trying to do this "careerist DJ" thing, because I was never really able to do so. So now, it's just down to what I actually like and what I actually want to do.

on production and practice

It's a really banal set of factors that spurred me into [writing the new album]. Basically, in 2023, I switched back to Mac. And so I got into my new MacBook, and suddenly, the latency on all the plugins I like to use was really low.

And I swear to God that kicked me back into gear because in the 2010s, I had my studio PC that I built out, and it was just this hodgepodge, and by the time it was 10 years old, 12 years old, things were really slowing down [performance-wise]. But suddenly, having this little MacBook that could just run things really smoothly without being plugged in, with headphones on, that quick iteration kind of thing—it got me going, and got me back, in a really natural way, into when I was really starting to learn about electronic music, and that mode where you're just staying up late, and you're trying things, and you're making patches.

Then I got really into this synth, Phase Plant, which is a soft synth, but it has this modular environment that's really intuitive—the way parameters can be linked to LFOs and different envelope followers. It's just a really nicely designed setup for designing patches. And for a long time I hadn't been interested in that part of sound design that's just simply making patches. [Music-making] for me has always been a huge mix of—Here's a patch I spent six hours on. But then this next sound is a preset, and this next sound is a sample. I was never precious about that kind of bespoke artisan sound design thing, but suddenly, I got that thrill out of synthesis again. I'm mostly pretty sample based. But messing around with envelopes and LFOs and just a different kind of reactivity in a soft synth, it was really inspiring for me.

I got a lot of mileage out of Phase Plant, and that just got my head back into it. Just making patches, giving them names, and not knowing what they're for. I love the idea of an album, or any kind of release, [being] something where you kind of do it fast, but maybe you do a lot of the sound-making and the instrument-making beforehand, right? So you [come equipped with] that toolbox. I was making patches where I didn't know what they were for, but there's a certain kind of feeling to them. There's a certain sensibility to them, a certain kind of movement as well. And then in my hustling post-COVID years, I also did a Splice sample pack. So that kind of forced me to make 300 samples, and that was a lifesaver at the time.

So, I suddenly had this sound palette, which wasn't necessarily what translates to the final version of the album, but just having those sounds in place got me going. It kind of frees you up, because when you're starting something from scratch and you're making everything from scratch, you can get pulled into the technical stuff. You can get pulled into the organizational stuff. But then just having the palette—because I can't really write music without the right sound. I can't just get a stock Nord piano sound and write some dope-ass chords, or do some epic finger drumming with the default drum kit. I have to have the patch that inspires me, and then, only a particular set of notes sound good on that patch. So that's the way I write the tune. It's really guided by what's going on technically.

And so when I transitioned from instrument design into trying to actually make music, I made a folder, and I called it "LP3." And then every time I would start a new project file, I would immediately save it. No matter how half-baked it was, I would save it as "LP3_A". And then what I worked on the next day was "LP3_B" and then, you know, I got down the alphabet. The first half of the alphabet was just absolute horseshit, but it was just the fact of—you're labeling things, and you're clustering them. It kind of has this journaling aspect.

It's like, there's this moment where I was trying to do something really stupid and ambitious, and then I save it, and I give it a little name, and then I come back three weeks later, and there's just a two and a half second moment in that project that's still interesting to me completely. And I'll just render that down, I'll flatten it, and I'll take that as a sample, and I'll just bring it to a new project. Everything else is just garbage. But you have to allow yourself to be making collections of things and labeling things, and naming things, even in a preliminary way—you just have to get your head back into it.

When you're registering things and keeping a kind of historical archive, it sticks with you throughout the rest of your day, and night, and sleeping, and all that. It keeps your head completely in that. It's putting these little markers so that you know when you're getting lunch later, you have it on your mind, because the file has a name or whatever. And it stays percolating.

That kind of marinating is super important for me. That early generative stage, you really have to set the conditions for yourself, because you're not going to be hyper disciplined, like—These are the contents of my mind right now, and it's going to come out the way I wanted it to. You have to build up that personal archive.

on sound design

I'm in this weird position where I'm sort of technical, but not technical where I can get really deep into stuff. I can get complex, but I'm not like a super audio tech-head person, I'm not an audiophile. But there's something about training your listening.

It's more about your ears. I'm always doing things in different ways, and I'm always starting over with how I do things, but there's the remainder—like what you have after time passes, is just what you're able to hear. When you have discerning hearing, even if you're working with new tools that you're not used to yet, or you're working in a non ideal environment, you're working on headphones, whatever it is that you've trained your ears on.

So even if you put me in front of a mixing board in a proper professional studio, I wouldn't know what to do with it. It's just more that I am sensitive to subtleties and to my own ears.

[The sound design on the record comes from] the kind of sound environments that I like. Even though I grew up on really different types of music, there was this kind of spatial aspect I was always really drawn to—like with dub techno, or "Y2K IDM," that kind of stuff. And then also "studio God" '80s music, you know, the sound-image, the sound-stage. Just the idea that you're not just placing instruments in relation to each other, but that they have a context.

And I really don't want to veer into being prescriptive about this, because it's really just my personal interest. I also love music that's just, like, no reverb, and it's just right on the top of the speaker. It's really just an artistic choice. And for me, I've been really interested in this kind of rich harmonic depth and spatial theater that I'm describing.

on changing monikers

This is the inevitable question, and it's another one that I wish I had a good answer for. Um, I was tired of typing it on a phone. [laughing]

Every promoter I've worked with, I have to write them, like, Listen, there's a dot at the end. I'm so sorry, but there's a fourth dot at the end.

So that 'M.E.S.H.' alias, I probably used it the first time around 2008 or so, playing at a house party, or a gallery thing in Baltimore. And then it was—remember that website Muxtape? I think I registered, "muxtape dot MESH" or something like that. I was making these weird deep house mixes and stuff. But yeah, it was just kind of inertia with that name, and because I had such a long break, I felt the need to to change it up a little bit.

But it's sort of like half changing it up because I'm naming myself after one of the albums that I put out. [laughing]

The whole artist name thing is so funny because in the '90s you could be some producer in Germany or something, and you have 18 different aliases for each micro genre. So you're doing hard trance, but then there's like, normal trance, and those are completely different aliases. And then people are buying records, and there's no social media, and so you can put out these aliases that are each their own thing. And now in our age, we have our social media accounts and you have to tie that to a handle, and that handle is your sole touchpoint.

My engagement with a lot of "underground music industry-ish business stuff" is limited in a lot of ways, mostly by choice. So I don't have the maneuvering room to be like, Okay, I'm gonna split off and do this other name, but it's okay because I'm doing a commercial for Audi so it’s okay if my audience doesn’t find it.

I live and die by being able to connect with people that appreciate my work. You know, it's a struggle. So this is maybe my way of changing my artist name, but in kind of a half-assed way.

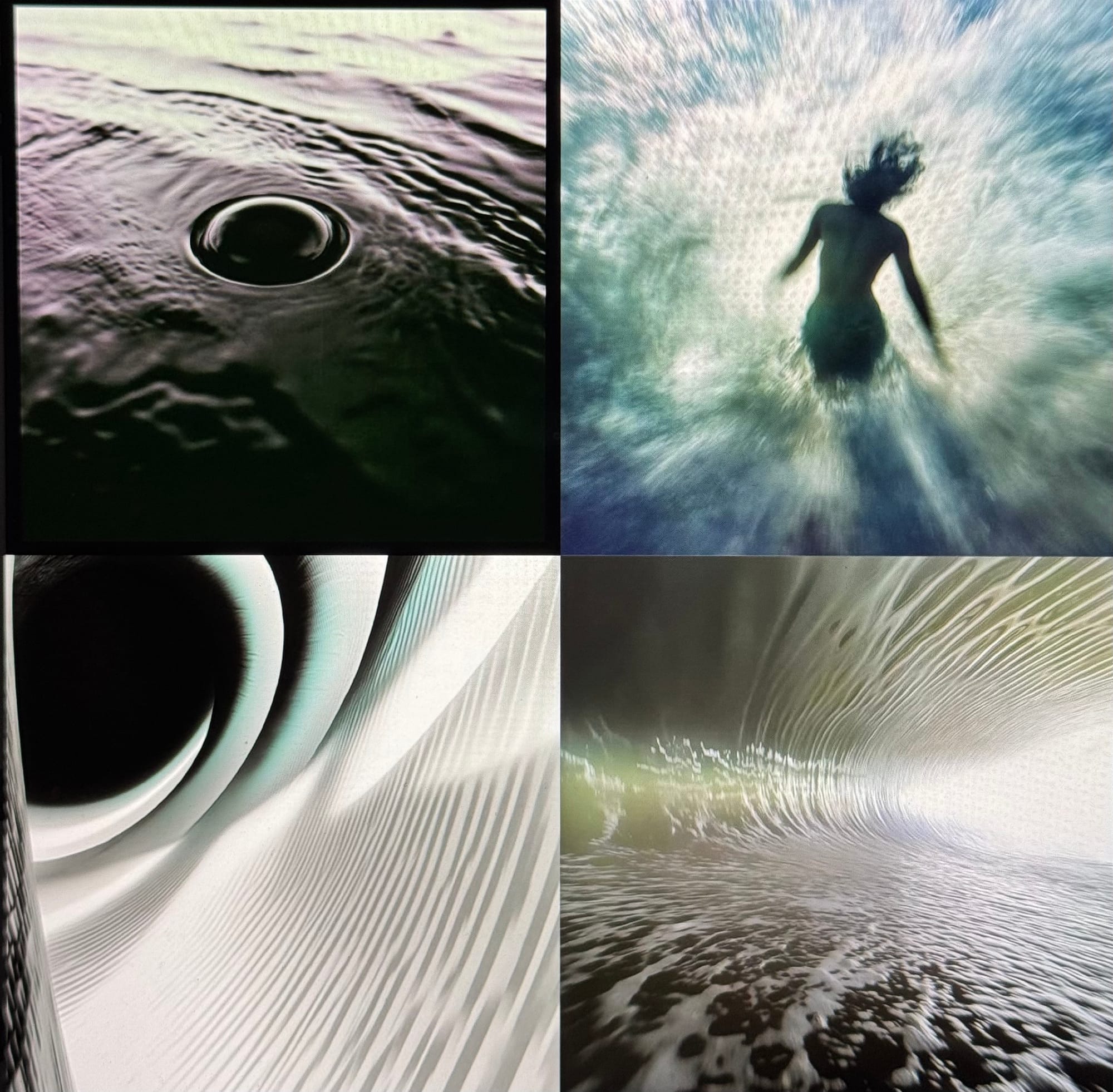

on artwork and visual design

It takes me so long to figure out visual stuff, because I always like to do things myself. So I do it in my own DIY way, but then, because I'm so particular and picky, it's a very, very long process.

There were seven, eight or nine different album covers. I changed it at the last minute—a few weeks before it came out. I wanted something quiet, that was serving the sound [of the album itself], you know. And I was concerned that that image wouldn't necessarily translate as a thumbnail, which is something you have to think about these days. But then it looked so good on YouTube, which is such a primo music listening experience when you use the semi full-screen theater mode. And it really looked great there.

[The artwork is] a composite. It's a composite photograph using real photographic material, and also some generative AI elements. When I finalized the track order, and I started to get a real feeling of what the album was evoking, it was really clear to me that it was the ocean, it was nighttime. It was dark, but not in a necessarily scary or evil way. You know, I grew up on the Santa Barbara Channel, basically looking out at the islands. So I was just maybe thinking about … dolphins at night. This might be my most Californian record.

on artistic growth

When you're starting out [as an artist or musician], it's sort of like you're reacting against the things that you don't like. [At the beginning of my career,] I was trying to do something more normal at the time. That's the tragedy of my older music, you know? I was really trying, especially on my early EPs, to make futuristic club music—where it was still playable [in a club context]. But then I just had my own tendencies, like I couldn't make exactly what I wanted. And there were these other things going on with what I was doing that I found personally interesting, that I just kind of pushed on. But then it wasn't very focused—because it's this very experimental thing, like I was figuring out how to make music.

And so, what I find with my older music is, there's this kind of—having a lot of ideas, and showing the listener those ideas: Oh, do you like this? Oh, well, if not, I've got this instead. You know, that's a very young thing. Because I wasn't working in the tradition of techno or house—where you can make your music fit into that POV, and then it just slots in with its slight variation on the theme. I was too incompetent to do something like that, even though it was what I wanted to do. So, instead, I was kind of pushing the things that were weird, and idiosyncratic, and personal to my own way of making music.

And I don't reject that stuff. But there's this sense of, you know, [my previous records aren't] something you can just kind of "put on." So with this [new record], it's my sensibility that's always been there, and my choices when it comes to harmonics, and rhythm, and things like that. But then it's sort of like—I'm giving things the space and time to kind of play out. I used to be so bad at repetition, like just allowing a groove to repeat itself, and so I was always missing that hypnotic effect, which is so important with music. To completely give into that grounding aspect—whether it's a drone, whether it's repetition—but the grounding aspect of music, I didn't have that. I had the ideas, and I had my angle with everything, but now, on this new record, it's about trying to bring in repetition and grooves.

I think this is my most accessible record. And I'm very, very pleased about that. It took so much restraint to be like, Okay, well, there's this rhythm going on, and I'm gonna leave it there for two minutes. But then when I think about all the music I love, they're like nine minute tracks, and then there's two or three things that happened during that duration.

It's just getting over that kind of ADHD thing. Like, looking at the default timeline in Ableton—so many of my older tracks are four minutes and 20 seconds long, because when something's at 135 BPM, based on my screen size at that time, that's how big the screen was. [laughing]

"Subdermal" from the new Hesaitix record.

A track toward the end of the record, "Subdermal," is funny. That track really came out of nowhere for me. But I'm realizing the inspiration. Because when I was 18, 19, 20, I was living in Portland, and I was listening to this website called "DeepRhythms.com.” And they would post these deep techno mixes. Everything from like, microhouse to dub techno. And I would listen to that all the time while playing Counter-Strike. A lot of that stuff is really embedded in me. And there's this particular Luciano track—it has this super picturesque chord pattern. And then there's this vocal sample, this guy saying "When the people will come," and then the chords are going off.

And it's just such a weird, elusive track to me. I love that early aughts, really precisely engineered, chord-heavy kind of electronic music. That track, "Subdermal," has this really repeating techno groove to it, and it has that kind of electro-style snare situation—very different for me, but I really enjoyed that one.

on vocals in electronic music

Electronic music is funny because, you know, it's usually purely instrumental. The human labor aspect is concealed, especially when it's a really digital sound. But then, you can make this sound, or this track, and then you title it, and then the title becomes very important—because the title is how your mind is framing that experience, and it can really set things off in different directions because there is no other textual information.

For the vocals on the record, I was thinking about language and its relationship to music and how important that is. And it changes for each artist individually. Some artists, it can just be like a string of numbers, and it totally makes sense. And then some others are a bit more personal, and it can get too much. So I was thinking about how I can bring in that kind of textual aspect, but it had to make sense.

What I did was I went back to all the vocal samples I'd used in the past, which are few and far between. Like on "Epithet" [Piteous Gate], it's just one word, a guy saying "epithet." And that was originally from a History Channel documentary about the Assyrian Empire or something. I wanted to have this kind of continuity [in the use of vocals,] because on the new record, there's a sonic continuity in terms of instrument design, harmonics, and stuff like that. So what I did was I trained generative vocal models on the vocal samples I used in the past, so that I could use that same voice with the same fidelity. But then I created a whole new vocal sample where I'm writing the text—I was actually doing vocal transfer where I would talk into the microphone, and then I would have this model of this dude speaking what I'm saying.

So on a couple of the tracks, there's that same guy, from "Epithet," and then "Captivated" on my first EP. It's like a History Channel narrative, and there's this very particular fidelity—like the sound mixing of a late '90s History Channel documentary, this booming American voice. There's something about that voice that's really evocative to me. I made a model of that guy, and then I can talk into the microphone and be that guy.

And then I was thinking, because this is a bit of a nostalgia record—I was thinking back to the history of, you know, electronica LPs. And by "electronica," I'm using that kind of tongue in cheek. I can say "trip-hop," I could say "IDM," I could say "ambient"—it's a little bit tongue in cheek, but I still believe it's effective. But I was thinking about this era of electronica albums where, when there was a vocal sample—maybe it was from a nature documentary, or it's Biosphere and you're hearing a recording from Twin Peaks, something like that. Or it's like a voicemail, like on a hip-hop record, like a skit. I was thinking about what kind of sound sources traditionally are in that kind of trope-y electronica universe. So I was making my own samples in that vein, but then they're completely engineered—like I'm actually writing the text of them in an engineered voice. I mean, that's just a little easter egg for myself, but I found the process interesting.

on reception and feedback

It's funny, because I had so thoroughly taken a step back [from music], and it's been really good to take that step back. And I'm really happy to be making music again, but I'm not sure exactly, in terms of where my effort and ambition is, how comfortable I am stepping back into touring again, and all that stuff. But [releasing this record] felt really good.

I got so many nice messages from people that I met a decade ago. Another cool thing was people writing to me, and I just knew their screen name, just from my mentions, you know, going back to the mid 2010s—people that were really sweetly and kindly favoriting my things on different platforms, yeah? And then I click on their profile, and a decade has passed, and they're doing their own thing in their part of the world, and their own thing looks really cool.

I kind of hated looking at my phone all the time, you know—just the whole release day thing of like, Here are my notifications. But it was really humbling that people responded to it. People cared and people listened to it, and listened properly. I'm just really grateful that people still cared enough to do that.

on what's next

Because I've held back for so long, I want to start putting out small things again. You know, I made my first website when I was 15 or something, and I made it in high school—I made a domain and a page in Dreamweaver, and I was making songs in FruityLoops, and I put them on my web page. I would FTP them to my little 100 megabyte server space.

So I have this desire to reconnect to that kind of direct experience of putting things online, because that was really formative for me. That was how I connected with people when I was young. And then I got pulled into this underground industry thing in the 2010s, which was really like a bubble in a lot of ways.

And so I want to reconnect to that immediacy of having an idea and just putting it online. I just feel really free right now—especially post-COVID, like, learning how to survive after the little dream of “being an artist" doesn't work out financially, right? So I've become really resilient when it comes to survival. Not to talk myself up, but we all have had to.

The thing with doing things on your own is, it takes a long time to get that traction. But when you're consistent—I've been thinking about this a lot, people that are lifers in independent music—people that stick with it, with all the changes in life, and industry, and stuff like that. But you keep doing something, and then eventually, you're just part of the story, because you've been doing it, and people know that you've been doing it.

It's really important to have that autonomy, where you're not just waiting for, you know, Red Bull to come back or something. You can't rely on stuff like that. So if you can, build your own audience, build your own thing. And it's what we all have to do.

But yeah, I feel much freer now, because I'm just doing exactly what I want to do. And if I'm going to do this for a long time, there will be times where I'm aligned with what people want or care about in that moment—and maybe I can, you know, play in Japan again, or whatever it is. And then there'll be moments where what I'm doing is less relevant, but I'm still going to be doing it. I really want to lean into that—just doing what I want to do and doing it 100%.