Words With Jefre Cantu-Ledesma: Root Strata, the San Francisco Scene, and Music as Gift

The roots of Root Strata and its S.F. scene; the genesis of "Gift Songs"; ambient music as phenomenon; the creative process.

I don't remember exactly how I discovered Tarentel, the hazy San Francisco post-rock band he founded with fellow guitarist Danny Paul Grody (whom I interviewed in 2016), but it probably involved combing through the "Experimental Music" racks at Amoeba San Francisco as a teenager. During the early '00s, when I was shopping from Aquarius Records at least once a month, I fell in love with The Alps, a cosmic space-rock trio that Cantu-Ledesma co-founded. Later on, I dove into his solo records, like A Year With 13 Moons, his first LP for Brooklyn label Mexican Summer.

In 2005, Cantu-Ledesma founded Root Strata, a solo effort that soon grew into a record label. Besides Tarentel, The Alps, and Cantu-Ledesma himself, Root Strata released music by a swath of Bay Area artists, including drone duo Barn Owl, noisenik Pete Swanson (of Yellow Swans), psychedelic guitarist Steven R. Smith, and Grouper, whose windswept folk music went on to wide acclaim.

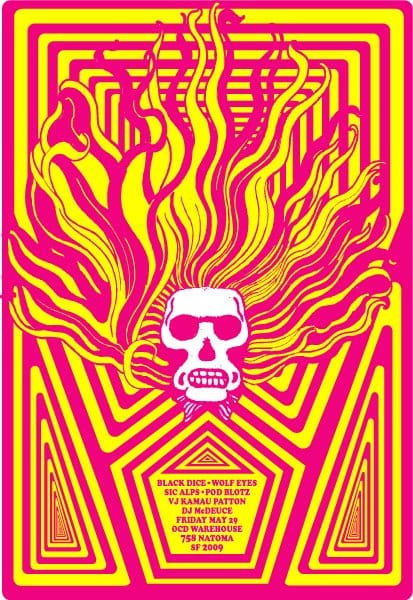

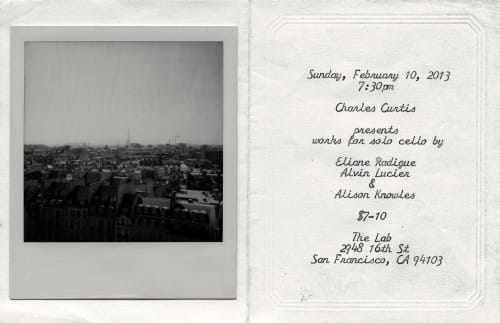

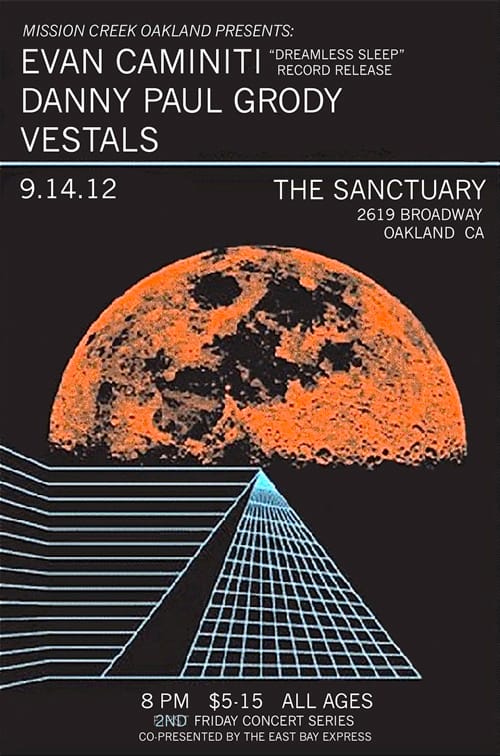

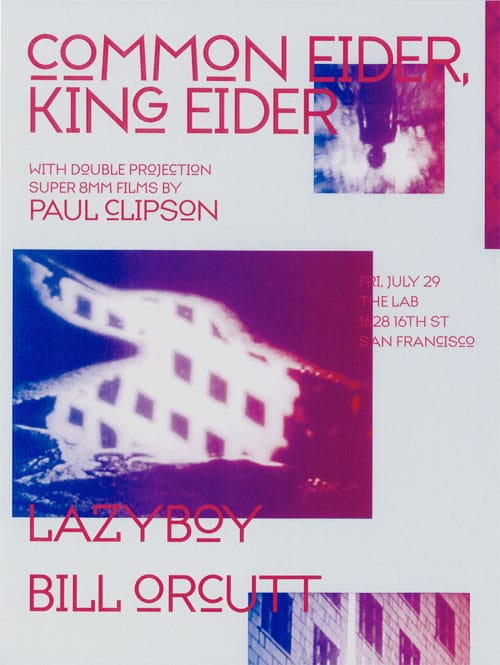

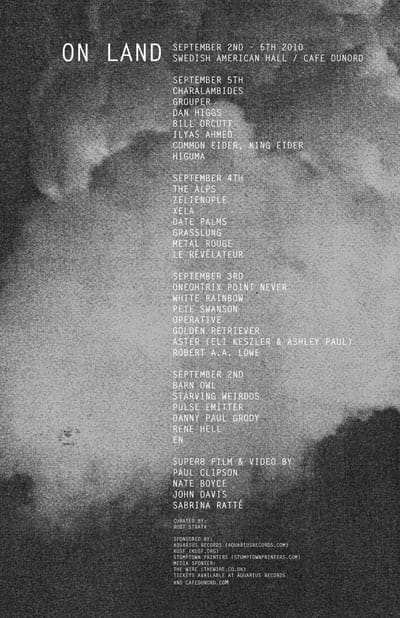

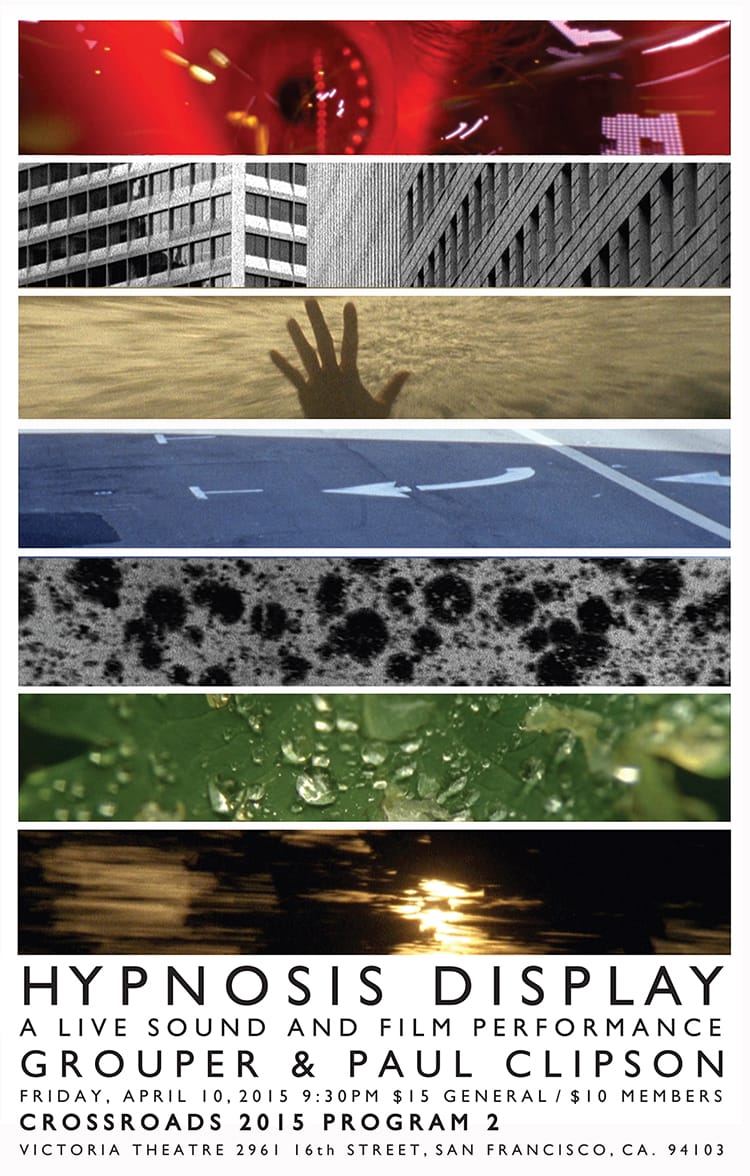

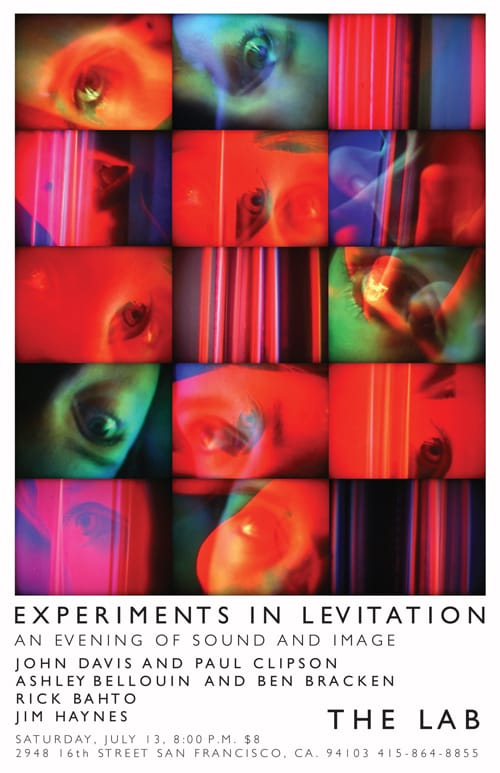

In time, Root Strata coalesced into a distinct West Coast scene, built around a collage of "ambient-ish" sounds that felt uniquely Northern Californian and Pacific-Northwestern: hazy, foggy, and spectrally beautiful, like the redwood forests the label was surrounded by. The show flyers interspersed below, sourced from the Root Strata website, serve as digital remnants of that scene and the community that surrounded it.

In 2025, Cantu-Ledesma returned to Mexican Summer to release Gift Songs, his first solo LP since 2019. It's an extraordinary work of minimalism that glimmers like a ripple in water—an approach that, in a certain sense, recalls the Root Strata days.

In March, I spoke with Cantu-Ledesma to learn the history of Root Strata and that particular moment in time in San Francisco—and how Gift Songs came together amongst the splendor of New York's Hudson Valley, where he now lives.

on the roots of Root Strata

If I remember correctly, in January 2005, Tarentel went to Japan. We were invited by Mono to go tour Japan. Around that time, I'm not sure why, but I just decided to start recording some stuff at home by myself. I pretty much had not done any solo work during the existence of Tarentel. You know, anything that I did at home by myself was then incorporated into Tarentel.

And so we went to Japan, just for a week. I recorded something, and then I can't remember what was first, like a chicken or the egg moment: I don't know if I recorded something and then thought, Oh, this might be nice to bring, as something to sell on the tour, or if I thought first, Maybe I should bring something, some solo music.

Past shows organized by Root Strata and friends.

Nevertheless, I recorded what ended up becoming the first Root Strata release, which was Voice Sutra. I made CDRs, and I printed some spray paint covers. At the time, I worked at SFMOMA, where I had worked for about a decade.

My office was in the basement. I was kind of a maintenance guy—not building maintenance, but more like office maintenance, and so I had this crazy space in the basement with my co-worker, who was also a visual artist. So we basically took over this crazy space. It must have been, like, 400 or 500 square feet, and I spray painted these covers, and that was it. And I took them to Japan.

I don't even really remember if I had the concept of "a label" at that time. But then, also, The Alps were active around that time, and I think we had a show coming up, so I was like, Oh, I'll do another CDR. And then Tarentel decided to do a 12 inch, which became the Home Ruckus EP. And, yeah, it just kind of had its own momentum from there.

I'm not one that, at least historically, has grand visions. I just have ideas that I think seem interesting, and then I sort of see what happens. And I've had many ideas that haven't gone anywhere. But, you know, Root Strata kind of became its own thing. It became its own sort of creature.

[We realized the label meant] having an avenue for The Alps, and then feeling like Tarantel could also have this kind of avenue, where we had more control over what we were doing.

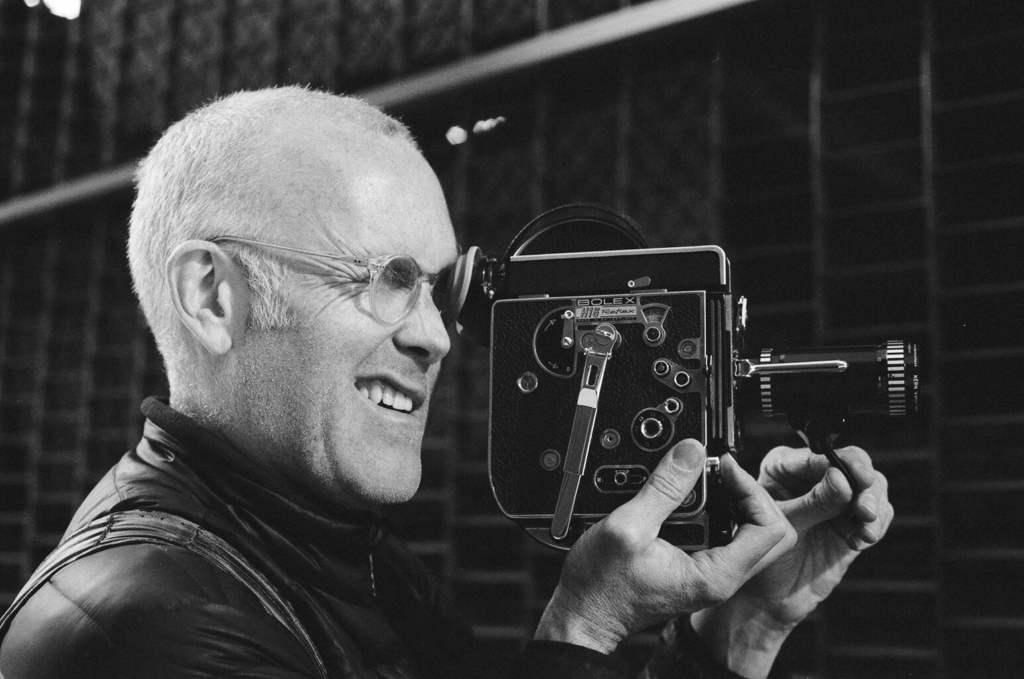

And it was also a very strange moment for Tarantel. We had a shift in line-up—we were back down to, I think, a three-piece plus Paul [Clipson, a San Francisco-based video artist who died in 2018]. So the idea of us having control over some of our outputs seemed interesting and more flexible, you know? And then some stuff went up on the first Root Strata website, and then people started buying it. That's when I realized, Oh, people are actually paying attention.

Past shows organized by Root Strata and friends.

Tarantel already had a name at that point, and had been around a little bit, so there must have been some people who were paying attention because Tarantel was involved. It just sort of blossomed from there and at some point, I thought, Who else can I support, right? You know, I didn't have too many grand ideas [for Root Strata] in the beginning, but I do remember feeling like, Oh, this could be a way to help new musicians—like becoming a platform for friends, or friends of friends.

[The early '00s] was a really interesting time. After 1999-2000, when the [first dot-com] crash happened, there was this wave of artists who seemed to move back to San Francisco. Rent was reasonable again. And it took another seven or eight years or so for things to get stupid again, maybe even 10 years, really, but I was gone [from San Francisco] by 2011 and definitely felt like things were changing rapidly.

on Root Strata live shows and the burgeoning scene

Back then, Tarentel was fielding a lot of [booking] requests from bands that were coming through, and those would typically have come through me. At that point, we all had connections with various spaces in the city.

[We were putting on shows at] The Hemlock [which closed in 2018], and at The Lab. I remember specifically putting on a performance for Charles Curtis at The Lab. That was years [after Root Strata was founded], parenthetically, but that was a fucking incredible show. There was also the Bottom of the Hill.

Outside of The Hemlock, we were doing house shows. There were some random places in Oakland. There was this place called Natoma Street, where our friend Tony, who had started playing with us, actually lived. And we did a couple of shows there. You know, it seemed like there was enough weird stuff happening that you could find a space for it to happen. And it wasn't a huge challenge if some band was coming through, and then, around 2005, that's when some people like Yellow Swans and Grouper and The Skaters and Tom Carter moved there. So it was really this sort of blossoming moment in music [in San Francisco].

[Around that time,] we did a lot of stuff on the Root Strata blog. I feel like the Root Blog is almost a different animal. It became its own thing. Just recently, [I was speaking with] someone that works at Mexican Summer, helping out with the new record, and we had a phone call, and he was like, You know, I just want to let you know how much the Root Blog had an influence on me. It sort of had its own life, you know, separate from the label.

I don't remember exactly when [Root Blog started], but Maxwell [August Croy], a friend who I had met in Seattle, moved from Japan to San Francisco, and he joined me and became an equal partner in Root Strata. He's a tech person, so he made the website. He was like, We should do a blog. And I said, you know, Great, sounds cool.

Past shows organized by Root Strata and friends.

And it just became another avenue for us, because when you're a label, you put something out maybe once every few months, but a blog allows you to have this [constant output]—I mean, there were periods where we were posting some every day. And it also became, Here are some things we find interesting, taste-wise, music-wise. it also became a place where we could promote shows, like all of Paul Clipson's shows. We promoted everything Paul did. We promoted it on the Root Blog, whether it was Tarentel related or not.

[We] built the platform ourselves, and people could comment, and we answered all the comments. At the peak, we were getting over 1000 [visitors] a day.

It's hard to have a sort of bird's-eye view on these things sometimes, but certainly from our perspective, it felt like there was a community of people that we felt connected with all around the globe. I mean, I have friends in Europe, I have friends in New Zealand and Australia, still, that I met through this wider Root Strata-Root Blog network.

[In San Francisco] in the '90s—it might have started in the '80s—right at 16th and Valencia was a thrift store on the bottom floor, and then above that, was a place called The Epicenter Zone. [A Salon.com memorial indicates the space was open from 1992-1999.]

It was a fully worker-owned and run record store, and we would put shows on there. And when I lived in Texas, they did a thing called The Blacklist, and you could order records from there, and they had short reviews, that kind of thing. Pre-internet, at least in terms of what the internet is now.

So I'd order records from The Blacklist, and I would order things that I didn't necessarily know what they were—but they would be like, If you're into that, then you'll like this. And then I knew it was all volunteer-run. So when I moved to San Francisco in 1994, I was like, I gotta go there—this will be a great way to meet people. So I did, and one of the people I first met was Gabriel [Mindel Saloman], who ended up being in Yellow Swans. Gabriel moved to Portland and started Yellow Swans, and then moved back to the Bay with Pete [Swanson]. I can't remember what year this was, exactly.

But at some point, I literally ran into Gabe on Valencia or Mission, and I said, What are you doing? He's like, I'm back. I'm playing music. And then Tarentel ended up playing a show with them and The Skaters in Oakland.

Past shows organized by Root Strata and friends.

And then it felt very much like there was some kind of cohesion happening in terms of weirder music, you know. I remember hanging out with another friend who now lives in Portland, and they were like, Oh, my roommate, Liz [Harris, aka Grouper], is playing. I think maybe it was a house party, and I think it was Liz's first show. And then I saw her [play live after that], maybe at The Hemlock—I can't remember, but she did play a show in San Francisco very early on. And then we had dinner, and I was like, I'd like to release a record of yours. That's how she and I first met, and we've been friends and collaborators since then.

[The shows we were playing back then were diverse in style.] Tarantel was certainly not ambient, right? I wouldn't say Yellow Swans either—they were pretty harsh. Other acts that were playing were like The Skaters, Axolotl, and Starving Weirdos would come down from Arcadia.

And if you look at the two lineups for the On Land festivals, which were 2009 and 2010, both of those were a mix. There were some acts that I would say were straight up 'ambient'—but I think it was a wide range of stuff. I think it was more an ethos we all shared than it was the specific kind of music we played, if that makes sense. It felt more kind of like we had some commonality around our experience, or the way we wanted to make music, or just the DIY aesthetic and doing things on our own.

By 2009, there obviously was enough momentum [around the Root Strata scene] that we were like, Oh, let's do a festival. You know, when you're in the thick of something, you don't necessarily reflect on it, right? You kind of don't know about it until it's over. [laughing]

[The On Land festivals] were great. They were at Cafe du Nord. The first one was September 2009, and the second one was September 2010. Both three days, like Friday, Saturday, Sunday. Paul [Clipson] did films for pretty much 50% of the bands, maybe more. It was constant—one band would play with his films, and then another band would not, and then the next band with, and so on. So for him, it was grueling. And there were other people doing film too.

We had people from all around. We had some people from New York. Eli Keszler came out—I can't remember how I met him. I think I just met Eli over email, and we invited him. We tried to get some international people. We invited Richard Youngs, but he couldn't come. But people from all around the [U.S.] came. It was really so DIY.

We didn't really pay anybody, either. It was really just a door split, and everybody was down. We were just straight up. We were like, We're not gonna make any money, and we'll split the door evenly. Maxwell and I had jobs and homes and we weren't working musicians, per se. But everyone was still game. We had Bill Orcutt play. Charalambides played. Grouper, too. Oneohtrix Point Never. Dan was a friend, so he played.

I left [San Francisco] in the spring of 2011. I was married, at the time, to a German woman, and she had to go back to Germany for visa purposes. I'd also just become kind of worn out by San Francisco. I needed a change in my life. I had been there since 1994, and I just needed to mix things up.

on the end of Root Strata

[By the time I left San Francisco,] I was getting the sense that the mood was changing. And then after I left, there just seemed to be a mass exodus over the next few years—to Los Angeles, and Portland, and New York. I mean, when I moved to New York City in the summer of 2013, Pete Swanson lived two blocks away from me, so people had definitely left the Bay and were landing in other places. And Oakland too, it was about that time when many people were moving across the Bay.

[Around 2017,] I don't remember exactly, [Root Strata had] slowed down. And then it was done. I didn't want to deal with streaming. I didn't want to deal with, you know, looking at data sheets from streaming and figuring out how much of this twenty-five cents goes where.

Past shows organized by Root Strata and friends.

So that was burdensome. That actually really burdened me, and neither one of us really wanted to deal with that. And the—I don't want to use the word market, but I guess that's the best word—the market changed in a way, you know? I think we could have continued, but we were selling fewer and fewer records. I mean, some of those last records we put out were fantastic, but we didn't have the money to do press, so we didn't have the same ratio of ambient exposure—no pun intended at all. [laughing]

Social media and all the different ways that people now learn about music, that ratio just started becoming asymmetrical in such a way that we were just barely popping above the surface. And that seemed unfair to the artists too. People were putting out just fantastic music that we really loved, but sometimes press people were like, Yeah, we need $5,000. And we weren't releasing people like Liz [Grouper] anymore—her records just sold themselves, right? So if you're trying to release some weird new band from Arizona that no one's ever heard of before, it's just too much market pressure.

So the whole project just started feeling not so fun. It wasn't flying anymore. It became more of a burden. And we never had the intention of it being just one thing—and it became its own thing, and then it was time to end.

on the genesis of Gift Songs

I've never experienced myself, at least in the creative process, knowing exactly where something's going. That's very true for this new record. This record—my now good friend, Joey [Weiss, who played bass on Gift Songs and recorded the album], has a studio here, upstate [New York, Hudson Valley], that he was putting together—and I knew about it, and [the studio] was kind of slowly coming together. We had known each other since maybe around fall 2000 or so. So, I knew about it, and he's like, Oh, you've got to check out my studio. And I was working on music which I wanted to do as my next record, which I was going to do by myself, which ended up becoming the Poverty tape that I did.

And when I was finished with that, I realized, Oh, I actually am not going to make a record out of this. This is just going to be this weird little one-off tape. So I was like, Joey, maybe we can try something together. His studio was really beautiful, and he was actually looking to get a bigger project to kind of get familiar with the studio—almost like a test case. And I was happy to at least try [working together] and see where things go.

Also, living up here, there are a lot of musicians up here in the Hudson Valley, and I'd started meeting people. So I met Omer [Shemesh], who plays piano, and I met Booker [Stardrum] who plays the drums. Clarice Jensen [who plays cello on the record], I'd already known, but she's up here too. So Omer and Booker and I went to the studio, and I just was like, Let's see what happens.

You know, the piece that eventually became "The Milky Sea" was the first thing we did. And it started with the drum beat, an idea for a drum beat. So Booker and I sat down and kind of worked it out together and it just kind of built from there—layer upon layer, layering very slowly over a few months. And then Side B, those first three songs on Side B, the "Gift Songs," Omer and I were the first ones to get to the studio, and we were waiting for Booker—so I was like, Omer, let's just sit down and jam. And those were the first three things that came out [of that session].

And I actually ended up overdubbing cello, and bass clarinet, and flute, and I was like, I'm going to take all that off. They were just really simple, and immediate, and really beautiful. And they just came out of thin air—so this idea of the gift of music, or the gift of creativity—it kind of falls upon you. You know, you gotta create the conditions, and then something just happens. And then there are other pieces that didn't make it on the record. Because, at some point, the record has to speak. My experience is, at some point, the record speaks to me. It says, like, No, this is what we're doing.

I really still value thinking about creating music in 20 minute chunks, because that's what fits on a record. Unless I know I'm doing something specifically for a digital format only—like, for Liz's [Grouper's] magazine that she does called Presence, I did an audio track for the magazine that's an hour long, which came out maybe last year.

So that was an instance where I knew: Oh, I could make a really long piece here. But when I'm thinking about a record like [this one] for Mexican Summer, or another label that I know that's going to do vinyl, I specifically think about the music being experienced in these 20 minute chunks.

So as "The Milky Sea" was developing, from my perspective, if "The Milky Sea" were six minutes long, it just would not have the same impact. It's not that interesting, right? When you add time to [a composition like this], it becomes interesting. It's not complicated. It's very simple: some guitars, and some shakers, and some drums, and a piano loop. There's an organ in there, too. It's not that it's musically complex, but when you throw in time, then for me—it becomes interesting.

So it's like, Okay, this is a 20 minute side. That's the only way this track's gonna work, as a 20 minute side. And then it was like, Okay, what could stand in relation to this piece and be interesting when you flip the record?—when you have that actual pause in space and you're able to turn it over, what would be interesting to the listener? For me, [thinking this way] frames the way that I'm creating—it's so helpful for me.

Otherwise you're just like, Well, I could do anything here, and then you end up with three hours of music. And it's helpful for me to say, Okay, I've got an hour and a half of music, and I can whittle this down to what feels essential and interesting—not just in its own right, but the "Gift Song" pieces are interesting as the beginning of Side B because of the just the total maximal overload of Side A.

I'm always thinking about things in this way. I studied painting and sculpture at the [San Francisco] Art Institute. I think about a record in similar terms of walking into a space to look at a visual art show: How are the paintings and the sculptures sitting in relation to each other? Curators just don't randomly put a sculpture in a room—they think about how those things work together. So I'm thinking about, How does this whole set of songs work in relationship? The last song is as important to me as the first song in relationship. You know, people might want to listen to "The Milky Sea" all by itself and never listen to the rest. That's fine. But when I'm creating it, in my mind, I have to sculpt this whole object. It's a whole object that I'm sculpting.

I feel like my records stand up to that, particularly the Mexican Summer records. They really stand up in a holistic, complete sense. They're each one piece, really.

on "ambient music" as genre and phenomenon

For me, a couple of things are coming up. One is making long-form music, which I think is really interesting in our particular technological moment, because of how we consume things, and inviting people to actually be with something in a longer, slower way. So that's one thought.

Another thought is because of the accessibility of music making—which I'm a huge fan of, but just because you can make a long form piece doesn't mean it's going to be that interesting to me, or draw me in on an emotional level. I mean, it's not hard to make a long-form ambient piece now. It's just not. But for me, when there's a texture to the music and a mood to the music, and it's hitting a particular emotional key, and it's in a particular emotional register—it's an "I know it when I hear it" kind of thing, you know? "The Milky Sea" is a perfect example. It started off with piano and drums—interesting, but not really good enough. Then it took months to add layers, and then to take things away. There's a bunch of material [we recorded] that isn't on the track, because you have to make those choices.

So that choice-making process, I think, is about cultivating a kind of discipline around really tuning in to what feels resonant and interesting in the creative process. And that's actually so much more difficult than it seems.

Ten years ago, these "Gift Song" tracks, I might not have felt that they were "done enough" to put them on a record. But the more that I make music, the more comfortable I am with certain ways of creating. Here's a perfect example: "The Milky Sea" took a really long time because I didn't know where it was going. I didn't know what it wanted to be for a long time. And these "Gift Song" tracks, I had no intention initially that they would be on a record or anything. Yet the simplicity and the immediacy of them speak to me in a way that's about—not overworking things, or somehow "sweating it" to make them "right." No, in fact, something can be good in an instant. Something can be spontaneously beautiful.

I mean, that's one thing that Paul [Clipson] really taught me. All of his work was made spontaneously in the moment. And so I've really tried to discipline my ear, more and more, towards things that are interesting. Not everything that I make is that interesting. That's why I don't put everything I make out. My high school art teacher said, "the artist edits." It's maybe the only thing I remember from high school. [laughing]

I create a ton of music. I create music all the time, just because I find it soothing and calming, and I just enjoy it. But I don't have to put it all out. It doesn't all need to be out in the world.

I saw this clip, maybe on social media, of Joan Didion. I think she was being interviewed by Charlie Rose. He was like, I heard this story that you would dissect Hemingway sentences, that you would sit down and take them apart. And she said, yes, she did that, and what she discovered was that initially, a Hemingway sentence feels so elemental, so basic, like we just ripped language down to the studs. But what that does is that [allows the reader] to become a participant in it, and you kind of create this meaning yourself. Your mind fills in the gaps, in a way, because not everything is being described to you. And I was like, Wow, that's a really interesting way to think about music-making, too. Allowing a subjective narrative to enter into a piece.

People that I don't know who have heard "The Milky Sea," maybe through press, have given me feedback, and I've thought in response, Oh, you're hearing all that you're hearing because you're bringing your own experience to it. Which is great. That's the ideal. That's the goal.

People are able to enter it without me, in a way. I can get out of the way, so that it's no longer about me, or the musicians on the record, or whatever. It's like a new shared experience, of a kind. So maybe I'm trying to create the conditions for a shared experience. Over time, I've learned to identify what's meaningful to me in the music-making process. You know, it's telling a story, but through my own particular language—which is almost exclusively just sounds.

on life in the Hudson Valley

This summer will be our fifth year living here. So I feel like a newbie, a little bit. I think what's interesting to me is that we are within close proximity of New York City. We go down [to the city] often, so that's nice. But then, you know, we're just deeply embedded in this rich, beautiful, stunning landscape.

In the fall and in the spring, you go on walks and you understand why there was a Hudson River School. It's just incredible. You can very quickly be in kind of a landscape where you're just overwhelmed by its beauty—maybe you're one of five people that's out there. I spent a lot of my early childhood in rural Texas, so I really feel this resonance with bigger wide-open spaces.

I play maybe one or two shows a year up here. [Performing] isn't a big part of my life here, but I'm connected with a lot of musicians—through new friendships, but there's also a number of musicians here that I've known for years.

Omer [Shemesh, who plays piano on Gift Songs] and Booker [Stardrum, who plays drums on Gift Songs] both live in the area, and I've also been playing with Ezra Feinberg. Check out his new record called Soft Power. He was also in a band called Citay, another San Francisco band. We reconnected in New York City, and now he lives up here, so we play weekly.

Living up here, it's just a very slow, quiet pace. And that's exactly what I need.