The music business is utterly enshittified. What's next?

Ruminations from the epicenter of Slopworld.

Weeks ago, my social media feeds were alight with a slew of posts from professional DJs describing landing at the club and plugging their USB stick into the industry-standard Pioneer DJ CDJ-3000, only to discover that their playlists of tracks were nowhere to be found—in fact, their USB sticks weren't recognized by the CDJ-3000 at all. In other words, through no fault of their own, these DJs were unable to perform due to a mission-critical firmware failure. Say what you will about the travails of being paid to travel around the world playing music in nightclubs, but it was a nightmare scenario in the literal sense: the DJ equivalent of showing up to class for a test only to realize you haven't studied any of the material and are completely unprepared.

Around the same time, the steady drumbeat of AI-generated music headlines began landing at a faster clip than ever. To wit: a pair of hilariously two-faced press releases from Spotify, exclaiming their "strengthened AI protections for artists and songwriters" while announcing partnerships with major record labels and rightsholders to "develop responsible AI products that empower the artists and songwriters they represent"—nevermind the fact that Spotify is already ground zero for AI-generated music slop. Which is what listeners want, it seems: per Billboard, "at least one AI artist has debuted in each of the past five [Billboard] chart weeks, a streak suggesting this trend is quickly accelerating." Turns out there's gold in those slop buckets, too: "Xania Monet," one of the fake slop-artists in question, was "signed" to a multimillion-dollar deal on a label led by a former Interscope executive. (What does it even mean for an AI slop-artist to get "signed" to a label? Who gets paid? Who knows.)

At a glance, these phenomena might not seem particularly relevant to the average music consumer. Most listeners will probably never touch a CDJ-3000, much less wrestle with malfunctioning software before DJing a packed nightclub. And while AI music slop is increasingly harder to ignore, it's still possible to avoid it altogether, at least for now.

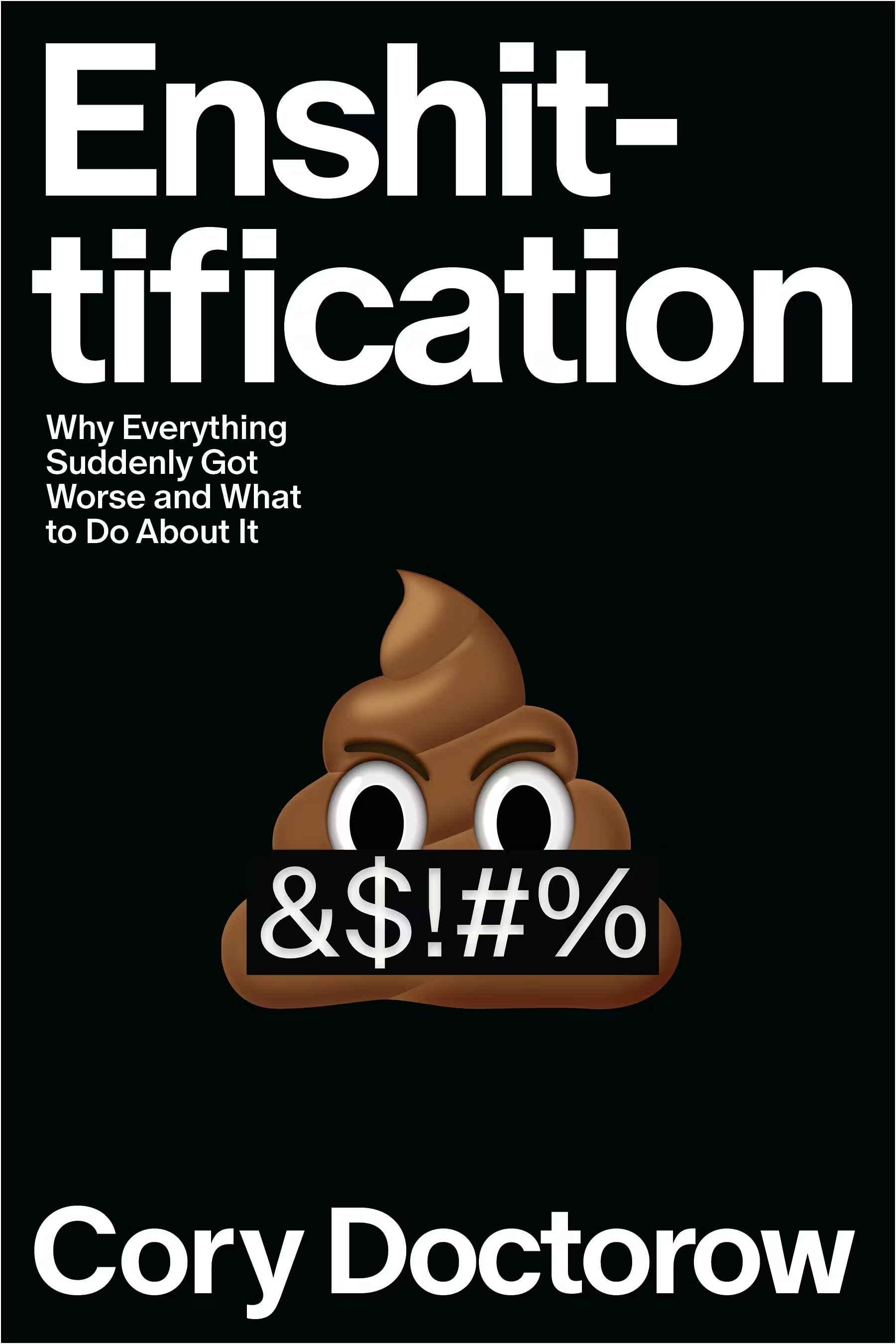

But both are pitch-perfect examples of enshittification, the bracingly vivid term coined by writer Cory Doctorow in 2022, and enshittification is swallowing the music business whole.

If you spend anywhere near as much time online as I do, you've probably encountered the term enshittification countless times over, whether or not you're familiar with Doctorow's essay. (He has since expanded the essay into a book.) In Doctorow's original conception, the term described the punishing experience of shopping on Amazon: wading through a labyrinthine morass of ads, knockoffs, and bogus results, fighting against the platform to find what you're looking for. Pithy and painfully relatable, the term went viral at once, making its way all the way up to the uppermost echelons of the blue-chip New York Times-Substack pundit industrial complex.

In a single neologism, Doctorow viscerally encapsulated the contemporary experience of life in America. We pay more, but get less; we have infinite choice, but they're mostly false; we stare at our phones and shout into the void, but we are desperately lonely and more disconnected than ever. Everything is getting shittier all of the time while a bare handful of astonishingly noxious manchildren have amassed more wealth than God.

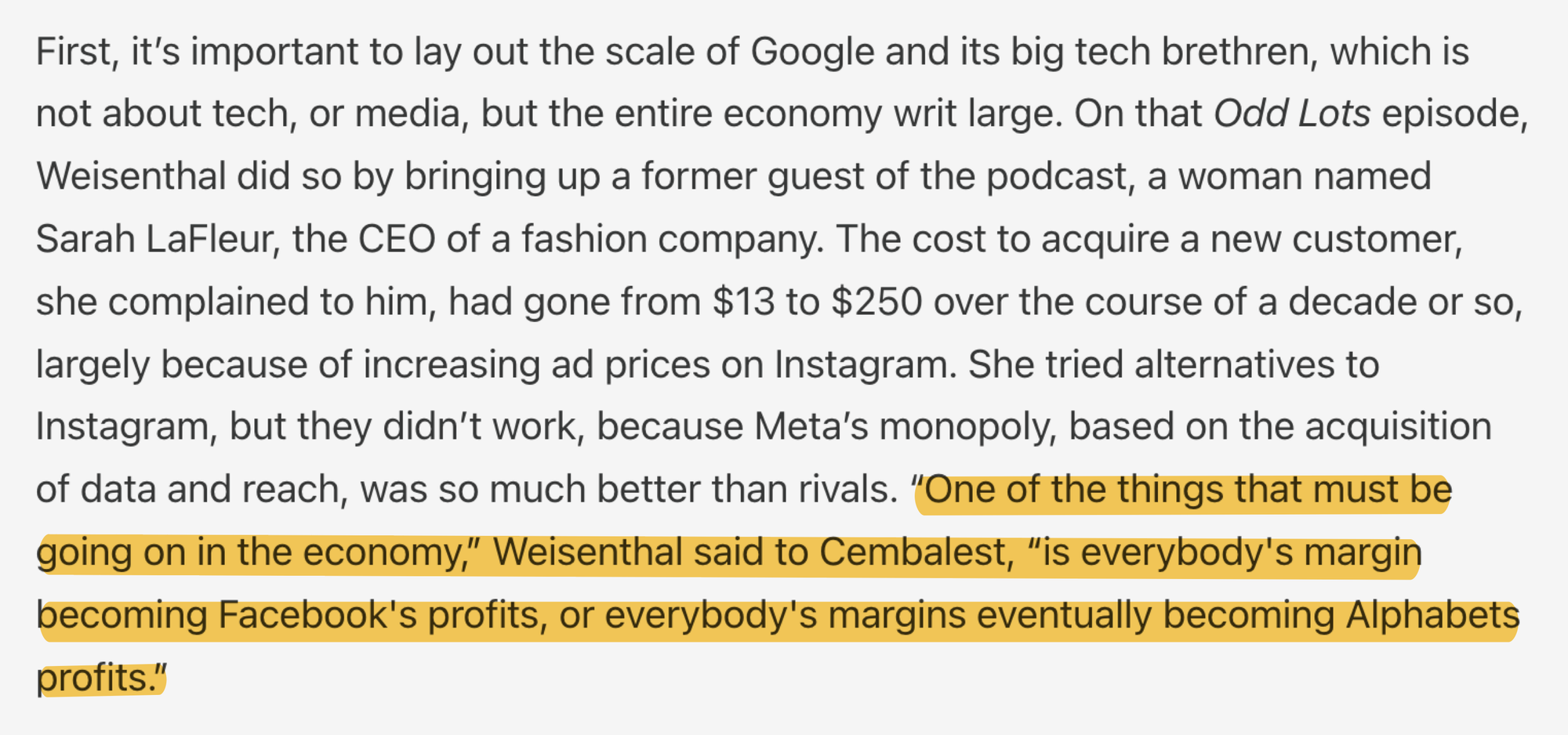

What Doctorow specified in his original essay, which sometimes gets lost in the mix as the term gains further purchase, is that enshittification is explicitly downstream of monopolization. The former is a function of the latter. In short, shopping on Amazon sucks because Amazon has choked its competition out of business while building a vertically integrated retail fortress in which sellers are forced to buy ads on Amazon's own platform in a desperate bid for customer visibility—simultaneously reinforcing Amazon's bottom line while driving consumer prices upward. Truly, the monopoly power that Silicon Valley wields is breathtaking, making the days of Standard Oil seem quaint in hindsight.

Since technological innovation and winner-take-all monopolization increasingly go hand-in-hand, perhaps it's no surprise that the music industry is so totally enshittified: the music business is fundamentally a technology business, after all. Pioneer DJ (technically now called AlphaTheta, a rebrand worthy of Cracker Barrel-esque derision) hardware is dependent on rekordbox, their own proprietary database software that allows users to analyze music, build playlists, and export tracks to USB devices; a new database format, in conjunction with untested firmware, triggered the aforementioned device failure. It boggles the mind that the global nightclub-festival DJ market is effectively in thrall to a single piece of janky software—"Don't update rekordbox, no matter what" is a running joke amongst DJ types—but that is late-stage deep-fried enshittified monocapitalism in action.

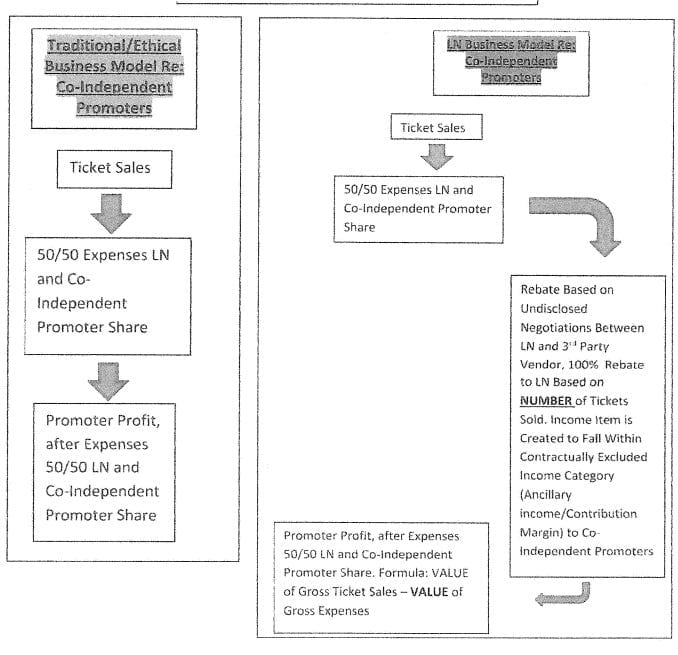

These are but drops in the proverbial bucket, of course. Live music has been so utterly enshittified by LiveNation, the vertically integrated venue owner-promoter behemoth whose business practices are brazenly illegal and anti-competitive, that the U.S. Department of Justice filed an anti-monopoly lawsuit against it. Buying a ticket to a show on Ticketmaster, the LiveNation-owned ticketing platform that controls at least 70% of the U.S. live events ticketing market, now requires you to check a box agreeing not to participate in class action lawsuits against them. (The jokes write themselves.)

The LiveNation playbook has proven so successful that other corporate conglomerates are putting it into practice themselves: Goldenvoice, the producer of Coachella and Portola Festival (and wholly-owned subsidiary of Anschutz Entertainment Group—whose namesake, Philip Anschutz, is a right-wing Christian billionaire who regularly donates to anti-queer organizations), has moved aggressively into the Bay Area market, producing events even at smaller venues that traditionally cater to independent promoters.

The thing about enshittification is it works like the classic frog-in-pot scenario: it's hard to tell exactly what's going on until it's too late to do anything about it. And as the pace quickens, it’s harder and harder to keep up. While writing this essay, Newsweek wrote that "The #1 Country Song in America Is AI-Generated," declaring that this top slop artist, "Breaking Rust," has over 2 million monthly listeners on Spotify, where they are a "verified artist"—verified how and by whom? Again, the jokes write themselves, etc.

It's impossible to keep up, and the especially tough part is to stop myself from falling too deep into the whirlpool of despair. On a daily basis, I ponder questions like:

Why is any of this happening;

Who wants this;

Why are software developers earning $300,000 per year to build rentier-class middleware and machine-generated slop spewing forth from an infinitely long hose;

And who is this for—any of it?

Truthfully, the music business has always been brutal, unfair, and unforgiving, "a cruel and shallow money trench … where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs," as the estimable Hunter S. Thompson once put it. ("There's also a negative side," end quote.) In the olden days, though, underground-ish and/or left-field music existed in its own parallel universe, a sort of bizarro-world micro-economy powered by tape trading networks, independent record stores, mailorder depots, vinyl DJs, and compact disc album sales. From the '80s through the mid '00s, it was feasible for small or mid-size artists and labels to turn a tidy profit—maybe not enough to live on, but enough to sustain operations, to pay for the next project and keep the ball rolling.

Ten years ago, I interviewed German artist Uwe Schmidt, aka Atom™ (among dozens of other aliases), a prodigious master of electronic music, to chat through a wide-ranging survey of his back catalog. The final tidbit of our conversation didn't make the final cut; I'm publishing it here for the first time:

Either you go full commercial or you go full underground—there's not really anything in between. In the '90s and most of the '00s, until 2008 or so, there was still a middle ground, you know. You could make underground music on an underground label and still sell 5,000 copies, doing something really weird. That doesn't happen anymore.

[The music scene] polarized into: If you do weird stuff, you do weird stuff—or you can do commercial stuff. That middle ground isn't there anymore, where you can be yourself, do your weird stuff, and make a living. OK, there's a couple of people still able to do that, but it's such a small niche—it's really tough. It's not easy to do that. In the past, in the '90s, it was a lot easier to make music and make a living.

— Uwe Schmidt (previously unpublished excerpt from A Guide to Atom™, 2015)

In 2015, when Schmidt and I spoke, Spotify had only been active in the U.S. market for four years, but the writing was already on the wall. Today, their capture of the U.S. music market is nearly complete. Because streaming now accounts for 84% of total music industry revenue—and Spotify is the clear winner amongst streaming platforms—it's no exaggeration to say that for many consumers, the notion of listening to music without Spotify simply doesn't exist. No matter how esoteric or off-beat, artists must now compete for listener real estate with the likes of Joe Rogan podcasts and fake machine-generated slop created by startups.

And yet the music coming out today, the music that I'm listening to, the music that I'm writing about is unfathomably good. Over the past five years, I've found countless records that surprise me, push beyond my expectations, and inspire me to rethink what I take for granted. It feels like no exaggeration to say that the music I'm discovering today is some of the best I've ever heard.

That's an unscientific conclusion, of course. Probably it's confirmation bias—since I'm writing about music again, I'm paying close attention to it—and maybe the afterglow of a particular kind of stasis I experienced during Covid lockdowns, where I relearned how to listen to music for its own sake, the consequence of no longer DJing with regularity. Even still, I've had the same conversation numerous times over the past year, with people I consider very tapped in: The music coming out today is really good, isn't it? — It sure is. So there you have it.

What is to be done, and what comes next? Individual action seems meager at best and hopeless at worst—nevertheless, ditching Spotify is a great start, if you're ready to give up convenience. (As I wrote back in 2016, pirating music is more ethical than streaming it.) Systemically and structurally, the situation is much more complicated. Streaming is here to stay; toothpaste cannot be put back into its own tube. What would a sustainable streaming economy for artists outside of the top 5% look like? What does "ownership" mean in the era of $40 vinyl LPs and digital platform subscriptions? Is "decentralization" truly possible—or even beneficial? Will there ever be a genuine alternative to Bandcamp?

I don't know the answer to any of these questions. What I do know is that it's entirely possible that I am wrong about all of this: the narrowing of options, the monopolization of digital and physical space, the algorithmic flattening of culture, the hyper-accelerated tide of AI-generated muck drowning out genuine creativity. Maybe all of this isn't enshittification, but simply a series of speed bumps along the road to new paradigms of artistic and creative possibility? (I know a whole lot of people in San Francisco, Berlin, and New York who believe this with their entire being.)

The other day, a friend showed me a video: "The only interesting AI music tool I've seen yet," he said. A team of researchers at IRCAM in Paris, calling themselves "ACIDS"—Artificial Creative Intelligence and Data Science—built a neural audio synthesis tool, trained on hours of TB-303 synthesizer sounds they recorded themselves, that translates input audio into acid-style 303 riffs. In their example, birdsongs are transformed into wiry, squelchy acid melodies in real time, as if birds were trying to recreate Aphex Twin's "Didgeridoo." The effect riffs on the "What if X, but Y?" meme energy that seems endemic to basically every present-day iteration of generative AI. But it's beautiful, too—and it flies right over the uncanny valley, bridging the natural and digital worlds.

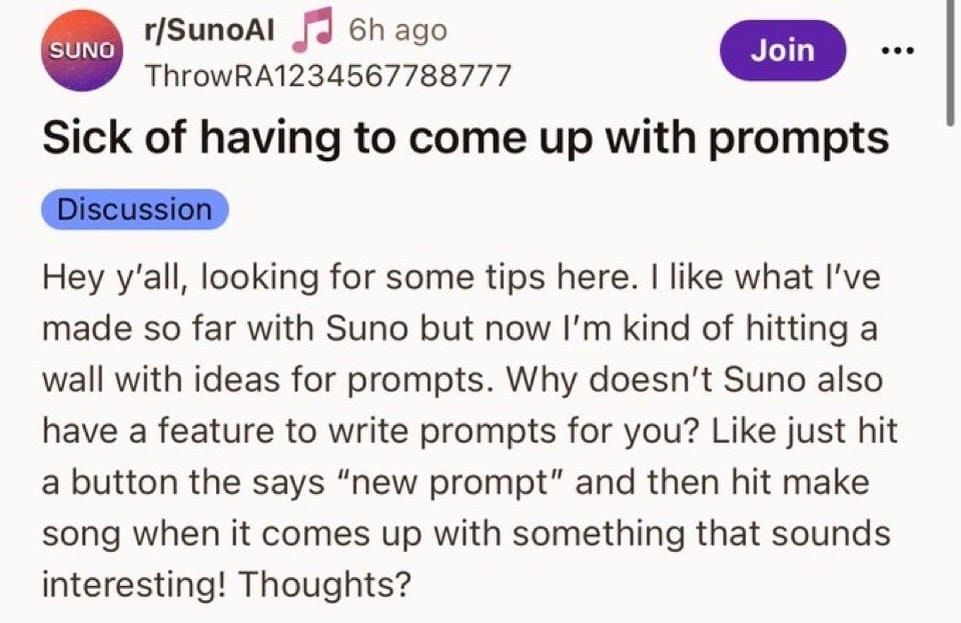

It's not lost on me that this tool, rife with genuine creative possibility, was built by a team of institutional data scientists in France, and is shared freely on GitHub with an open-source license. Meanwhile, here in Silicon Valley, where venture capital is the strict arbiter of the possible, the future of music is being written, prompt by prompt, by startups like Suno and incubators like Google DeepMind—whether we like it or not.

One of these approaches will likely dictate what the next decade sounds like. I wonder which it will be.